With the 2020 election approaching, each week brings a new set of presidential poll results. As perennial as the election cycle itself, the arrival of early data is accompanied by analysts and forecasters wrestling with its value. In particular we wonder how much early polling can tell us about the general election, given that so many factors — the state of the economy in 2020, the identities of the ultimate candidates, and all manner of campaign-related events — are still in flux?

Common wisdom, backed up by decades of data, is that early general election polling is not to be trusted. For example, an analysis by Harry Enten found that between 1944 and 2012, polls conducted a year out from a presidential election had an average absolute error of about 11 points. Similarly, Robert Erikson and Christopher Wlezien’s analysis of several decades of polling data found that polls had relatively little predictive power until later in the campaign.

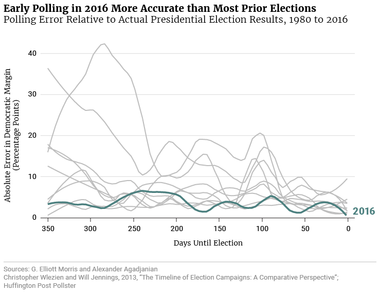

While the average track record for early polls is unimpressive, analysis of recent election cycles tells a slightly different story. In their analysis of polls since the 1980 presidential election, George Elliott Morris and Alexander Agadjanian found that early polling has been notably better at predicting final election results in recent elections. For example, they report that polls fielded 300 days before the 2016 presidential election were off from the final result by about four points.

In fact, if we look at the accuracy of polls conducted over the course of the 2016 election, early polling was only marginally worse than polls conducted during the final stretch of the race. Early polls in 2012 performed similarly well.

New data from the 2019 VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) also suggests that early polls may now be more predictive than they were in previous cycles. Here’s why: while many things contribute to the value of early polling, one significant factor is how accurately Americans can predict their own behavior. Put simply, if you ask people how they are going to vote in advance of an election, how many have made up their minds in advance and how accurate are those responses? All else equal, if the number of people making early decisions that are consistent with how they actually vote goes up, early polls should be more accurate.

This early decisiveness is precisely what we see in the data.

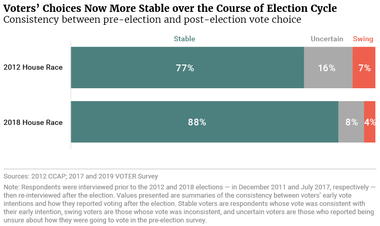

In December 2011, the Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project asked Americans who they were going to vote for in the 2012 congressional race in their district. Those same individuals were interviewed again after the election and reported how they actually voted in those races. Of those who eventually voted in 2012, about three-quarters (77 percent) could be classified as stable voters — voting in a manner consistent with the preference they expressed in December 2011. Fewer than 1 in 10 (7 percent) were swing voters — voting in a manner inconsistent with their earlier preference — while 16 percent were uncertain how they were going to vote that early in the election cycle.

By contrast, Americans were far more decisive and stable during the 2018 election cycle. In July 2017, these same Americans were asked who they were going to vote for in the 2018 congressional race in their district. Once again, respondents were interviewed after the election and reported how they voted in those races. Of those who eventually voted in 2018, almost nine in 10 (88 percent) were stable voters. Despite pre-election preferences being measured even earlier in the election cycle — July 2017 vs. December 2011 — there was an 11-percentage-point increase in the number of stable voters between these elections. Compared to the 2012 election cycle, about half as many respondents were swing voters (4 percent) or uncertain how they were going to vote prior to the election (8 percent).

While the data does not point to an immediate cause for rising stability, these findings are consistent with other political science research. In short, the Democratic and Republican parties are presenting increasingly clear choices to voters — distinct platforms with more readily understandable consequences. In turn, American voters have become more decisive in their judgements of the parties and more consistent supporters of a single party. The findings presented here are plausibly explained by these developments.

Certainly, voter stability is one factor among many that affects the accuracy of early polls. As voters become more stable, it could well be that other factors work in the opposite direction. Still, the information presented here suggests that analysts who might otherwise dismiss early poll performance reassess some of their assumptions given the increasing stability of American voters.

Robert Griffin is the research director of the Voter Study Group. Views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the collective Voter Study Group.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.