Democratic Norms, Ideology, Political Parties

In recent years we have witnessed a rising number of physical confrontations at campaign rallies, in politically motivated attacks, as well as hate crimes and violence motivated by conspiracy theories. For many Americans, the conflict surrounding the 2020 presidential election feels like a powder keg ready to blow.

These tensions are already coming to a head in the form of armed partisan protests against the widely supported coronavirus mitigation policies — protests organized and supported by some Republican leaders. Many protestors at these small gatherings ostentatiously carried assault rifles in an effort to intimidate government officials into responding to their unpopular views, and some even tried to force their way into secure rooms in state capitol buildings. Do these armed displays reflect the violent inclinations of a few dangerous cranks, or do they reflect a broader public openness to partisan violence?

Political parties are traditionally understood as organizations that effectively manage disagreement within the political system. But once partisans begin treating their opponents as enemies, partisan differences may instead encourage democratic breakdown. Have we reached the point where parties are more of a force for chaos than order?

In this combustible context, it is important to assess what the public thinks about political violence. The answer is important for gauging partisan hostility, for mapping the environments that may encourage individuals to harm others, and for understanding who is most likely to act out politically motivated aggression — from low-level harms in everyday life to rare deadly attacks. The stakes are high: Healthy democracies forgo violence and accept democratic norms and institutions as the only legitimate means for resolving political conflicts.

New data from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group sheds light on this important topic. The December 2019 VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) was conducted from November 22 to December 23, 2019 and included questions specifically designed to measure partisan hostility. The results suggest that the American electorate contains a small but substantial number of partisans who approve of threats and violent action against their partisan opponents.

In prior research, something known as a “feeling thermometer” has been the conventional measure of partisan animus. Survey respondents rate each party on a 0 to 100 scale, from cold (unfavorable) to warm (favorable) feelings. The gap between ratings of one’s own party versus the other party is called “affective polarization.” This is a type of polarization based on unfavorable feelings rather than differences over policy. On average across the entire American public, that gap grew from 15 percentage points to 30 percentage points between 1972 and 2012, a phenomenon driven mostly by people who have social identities (e.g., race, religion) that match their own party’s base.(1)

To be sure, feeling thermometers are useful for judging general dislike and its national change over time, but they are poor measures of hostility. The vitriol we hear today is certainly not well-represented by the relatively bland score of zero on the thermometer scale.

To address these shortcomings and to directly answer concerns about growing violent animosity, we have been fielding survey questions on partisan threats and violence since 2017. A battery included in the December 2019 VOTER Survey provides the latest snapshot of these extreme views.

This battery included four questions. To help ensure respondents’ answers were as relevant as possible, we framed these questions about partisan conflict now and not some historical or imagined dystopian scenario. Two questions were about threatening opposing partisans — both leaders and ordinary citizens. The other two questions asked when violence is appropriate today and based on the 2020 election outcome.

So, for example, someone who identifies as a Democrat or as an independent who leans toward the Democratic party saw these four questions:

Respondents who identify as Republican or as an independent who leans toward the Republican party received questions that flipped the partisanship in each question.

We find that responses to this partisan hostility battery are weakly and negatively correlated to respondents’ thermometer rating of the opposite party (correlation coefficient equal to +0.17) and to the combined affective polarization measure (-0.13).

These results suggest that the relationship between the two measures is inconsistent and that, to the extent there is a linear relationship, it runs in the opposite direction from the one we would expect. Those giving lower thermometer scores for opposing partisans and those with high affective polarization are less likely to express partisan hostility.

In short, the traditional manner in which partisan animosity has been measured doesn’t capture these violent extremes in substance or by proxy.

(1) Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity by Liliana Mason, co-author of this blog post: www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/boo....

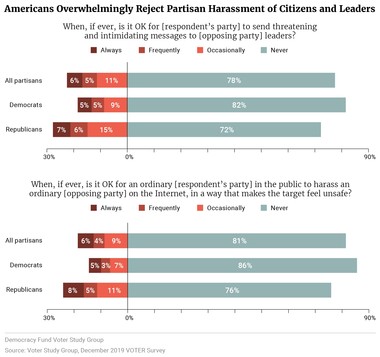

From the start, we see that most of the public rejects partisan threats and violence. Between 72 percent and 88 percent of the public chooses “never” or “not at all” in response to these individual questions. Even so, a small but substantial minority indicates some openness to partisan threats and violence across these measures.

On average, Americans are slightly more comfortable threatening party leaders than ordinary people. Among all partisans, 22 percent believe it is at least occasionally warranted to threaten leaders, while 19 percent believe it is at least occasionally acceptable to threaten regular partisans online.

In the case of sending threats, we find a difference between Democrats and Republicans. When thinking about sending threats to leaders, 19 percent of Democrats and 28 percent of Republicans believe it is at least occasionally acceptable. When it comes to harassing regular partisans online, 15 percent of Democrats and 24 percent of Republicans believe it is at least occasionally acceptable. We should note, however, that this partisan asymmetry has not consistently appeared in previous surveys we have administered, so it may not replicate in the future.

Figure 1

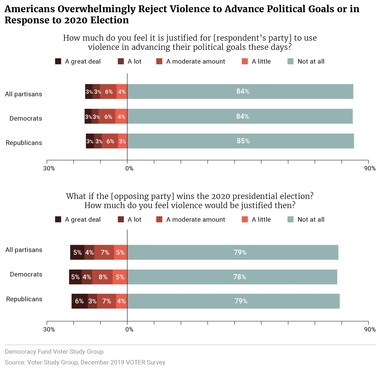

On the question of outright violence, Americans are slightly more subdued. Only 16 percent of Americans believe that using violence to advance political goals would be even “a little” justified. This number is essentially equal among Republicans and Democrats. When asked to think ahead to the possibility of losing the 2020 election, that number grows to 21 percent of Americans. Republicans and Democrats are again basically equal in their approval. For both parties, losing power through elections makes alternatives to elections more palatable.

Figure 2

These relatively small percentages of respondents who endorse partisan threats and violence theoretically represent tens of millions of Americans. However, violent views do not mean these people are likely to behave violently. The vast, vast majority will not, despite their views, because of the norms and laws proscribing violence. We still worry, however, because these Americans may still engage in lower-level aggressive behaviors that contribute to a broader environment encouraging violence by others.

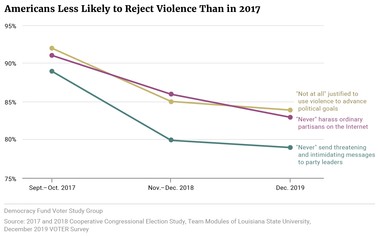

Unfortunately, the American electorate appears to be growing more open to threats and violence in recent years. Since 2017, the percentage of partisans saying “never” to threatening leaders fell 10 percentage points, those saying “never” to threatening citizens fell eight percentage points, and those saying “not at all” to partisan violence today fell eight percentage points. Most of the changes occurred between 2017 and 2018.

We suspect these trends might continue as the 2020 election approaches and partisan vitriol reaches a fever pitch. Responses to the current COVID-19 pandemic could also have an effect. Past research indicates events that reframe politics in terms of national unity can reduce partisan hostility. However, that depends on leaders who won’t aggravate divisions in a crisis. What we have seen early in this crisis seems to lean more toward the latter.

Figure 3

How seriously should we take these views? Sometimes people answer survey questions expressively. This means that they don’t really believe their reported answer; they just responded in a given way because it felt good to say, or because they wanted to indicate support for their team.

In past studies, we’ve asked respondents directly whether they say negative things about opponents “because it feels good” or only because they “firmly believe” them. Overall, 18 percent of those who supported threats and violence said they were mostly or entirely doing it because it feels good. The rest claimed sincerity.

In other studies, we’ve been able to identify factors that predict these violent attitudes. Support for political threats and violence are highly correlated with measures of “aggressive personality.” People who tell us that they have been in physical fights and are easily angered are also more likely to support political threats and violence. To us, this suggests that these measures are connected to some real-world behaviors.

In short, we’re confident that most partisans who have extreme views are serious about those views, even though few will act on them without some additional impetus.

Assuming these responses are true expressions of extreme views, what can we do to help prevent political violence?

Senior Fellow Rachel Kleinfeld at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace summarizes research on political conflict around the world to suggest several proactive steps.(2) First, we can reduce violent attitudes by emphasizing community norms against violence within each group. Political leaders have a particularly large responsibility to direct their followers away from violence, rather than fanning the flames. For example, Fox News personality Sean Hannity, recently set a vital standard by condemning the threatening and “dangerous” display of guns in coronavirus mitigation protests.

Government institutions and community groups can also inhibit spirals of violence by preparing de-escalation plans for implementation after attacks. Journalists can play a role too, by refraining from framing every political event as a zero-sum win or loss for one party or the other.

Partisan-motivated violence isn’t new in American politics, but it has been rare in recent decades.(3) Recent developments have changed that, however, as partisanship has aligned more strongly with deep racial and religious conflicts that have divided Americans throughout history. While parties are an essential organizing structure of democratic government, they can also undercut stability and legitimacy when they inspire extreme undemocratic behaviors among their followers.

Understanding radical partisan attitudes and actions is key to preserving and defending our democracy. We plan to continue our efforts mapping these views, identifying their origins, and seeking democracy-building solutions in 2020 and beyond.

(2) “A short primer on preventing political violence” article in The Washington Post: http://www.washingtonpost.com/....

(3) With Ballots and Bullets: Partisanship and Violence in the American Civil War by Nathan P. Kalmoe, co-author of this blog post: https://www.cambridge.org/core....

Nathan P. Kalmoe is an assistant professor of political communication at Louisiana State University in the Manship School of Mass Communication and Department of Political Science and author of With Ballots and Bullets: Partisanship and Violence in the American Civil War.

Liliana Mason is associate professor of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland, College Park, and author of Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity.

Views expressed here are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the collective Voter Study Group.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.