Ideology, Immigration, Political Parties

The 2016 campaign and the Trump presidency has focused on issues tied closely to Americans’ racial, ethnic, religious, and gender identities — and generated calls for both parties to reject “identity politics.”

The challenge for both parties is that identity politics is increasingly baked into American politics. Even if Democratic and Republican candidates try to avoid it, voters are increasingly divided by identity-inflected issues that remain salient to their choices at the ballot box.

Data from the most recent VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) provides a unique window into this growing partisan divide because it tracks the same respondents over time. On many identity issues, Democrats and Republicans have not differed greatly in the past. But today they are much further apart. For example, Democrats and Republicans now differ much more on the extent to which they believe racial inequality is due to structural forces and discrimination rather than the individual behavior of black Americans.

This partisan divide extends to immigration as well. Among the roughly 3,700 respondents who have been interviewed in all five waves of the survey, partisan differences are expanding. In the first wave, conducted in December 2011, a similar number of Democrats (51 percent) and Republicans (48 percent) favored making legal immigration easier or no change (as opposed to making it harder). But by December 2018, more Democrats (67 percent) and fewer Republicans (41 percent) held this position. As a result, the divide between the parties grew by 23 percentage points.

The same growing divide emerges on questions about the contributions of undocumented immigrants as well as whether they should have a path to citizenship. In both cases, this is largely due to movement among Democrats, many more of whom now believe that undocumented immigrants make a positive contribution to American society. And the increase in support for a path to citizenship, although visible among both parties, is about twice as large among Democrats. Other surveys show the same partisan polarization.

This growing partisan divide on immigration issues is not mirrored in every issue. Although Democrats and Republicans increasingly diverged on whether to expand the Affordable Care Act, they did not diverge as much on whether “it is the responsibility of the federal government to see to it that everyone has health care coverage.” And the partisan divide on whether to raise taxes on the wealthy (those making $250,000 or more each year) actually shrank.

There are two possible explanations for growing partisan divide on immigration: Americans could be shifting their party identification to “match” their views on this topic, or they could be shifting their views to match their partisanship. In this case, the latter appears to be true. Even though many people possess stable attitudes toward racial and ethnic outgroups, partisan identities appear to take precedence.(1)

What’s more, Americans’ views of immigration have become more important to the choices that they make at the ballot box. This was true in the 2016 presidential election, for example. And it was also true in the 2018 congressional election.

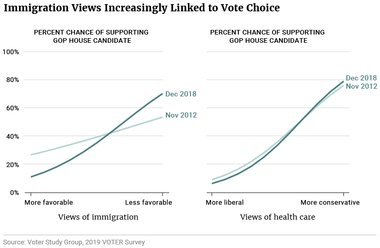

The VOTER Survey allows a useful comparison between the 2012 and 2018 congressional elections. (There was no interview in 2014, unfortunately.) In each year, respondents were asked whether they supported the Democratic or Republican candidate in their U.S. House district. I modeled voters’ choices as a function of three factors: their party identification, their attitudes toward immigration (a scale based on the three immigration questions referenced above), and their attitudes toward the government’s role in health care. All three factors were measured in the December 2011 interview.

Attitudes toward immigration did become more strongly linked to voting for the U.S. House. In 2012, a hypothetical shift from the most favorable view of immigration to the least favorable view was associated with a 27-percentage-point shift in the chance of voting for the Republican House candidate. In 2018, it was associated with a 59-percentage-point shift.

Meanwhile, the association between health care attitudes and congressional voting, while powerful, was not much larger in 2018 than 2012 — even though it was the top issue in Democratic candidate advertising and the second most prominent issue in GOP candidate advertising. Thus, even if congressional candidates in 2018 sought to focus the election on health care, immigration loomed larger — more so than it had six years earlier.

Was the larger apparent effect of immigration attitudes in 2018 due to the salience of the migrant caravan that dominated headlines in the weeks prior to the election? It doesn’t appear so. The relationship between immigration attitudes and congressional voting was no larger in the post-election survey than in an earlier VOTER Survey in April 2018, which preceded the caravan news coverage. (Other scholars have found the same thing.) Instead, the importance of immigration at the ballot box likely reflects the nearly chronic attention directed to the issue during the Trump presidency.

Since the 2018 campaign, immigration has continued to figure into political debates on a regular basis — with ongoing news coverage of the influx of asylum-seekers, the deaths of immigrant children in U.S. custody, and other stories. Of course, a major and unrelated event — such as a recession — could push immigration out of the news and focus the presidential campaign on the economy. But even then the underlying partisan divide on immigration would remain ripe for continued conflict at any point in time.

(1) This finding is based on cross-lagged models of the panel data in which partisanship and immigration attitudes in one survey are regressed on partisanship and immigration attitudes in the previous survey. For a similar analysis of racial attitudes, see Engelhardt, Andrew M, 2018. Vanderbilt University Working paper, "Racial Attitudes through a Partisan Lens," Available here.

John Sides is a professor of political science at Vanderbilt University and member of Voter Study Group. Views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the collective Voter Study Group.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.