Key Findings

Free and fair elections are the lifeblood of democracy. They give voice to the American public and help channel the will of the people into policy and the direction of the country. Perhaps just as important is Americans’ faith in election outcomes. If a losing candidate and their supporters do not accept the result, it undermines the legitimacy of the government and the foundations of our polity.

Despite Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 election, which has not been challenged in any credible way, President Donald Trump failed to concede defeat and spearheaded a conspiracy-laden campaign to discredit the results of that election. A group of his supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, in a failed attempt to stop the certification of Biden’s election. These actions represented a stark violation of a long bipartisan tradition of peaceful transition of presidential power and have raised concerns about the stability of our democracy.

It’s worth appreciating that claims about voter and election fraud are not unique to the Trump era. After the 2004 election, for example, some Democrats suggested that voting machine manufacturer Diebold, whose CEO was a Republican donor, had rigged the results for President George W. Bush. And during the 2008 presidential election season, the McCain-Palin campaign accused left-leaning nonprofit ACORN of “massive voter fraud.”

However, the 2020 presidential election has been singular. In the run-up to Election Day, President Trump made wild and unsubstantiated claims about fraudulent mail-in voting and attempts by the Democratic party to steal the election.(i) The election season was then capped off by an unprecedented, months-long campaign by Trump and significant portions of the Republican party to cast doubt on the results of the 2020 election — a campaign of lies that has continued to this day.

The question is, how different was 2020 relative to earlier elections, and how worried should

we be going forward?

New data from Democracy Fund + UCLA Nationscape™ and the Democracy Fund VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) suggest that voter confidence in the 2020 election was indeed different — and that continued doubts about election integrity among many Republicans raise concerns about the future.

In the aftermath of previous elections, researchers have frequently found partisan divisions in how people view the fairness of the election and the legitimacy of the incoming president. In large part, these differences are driven by individuals reacting solely to the election’s outcome — with supporters of the winner expressing higher levels of confidence in the results and supporters of the loser expressing lower levels of confidence

There is evidence that this occurred in 2020 as well.

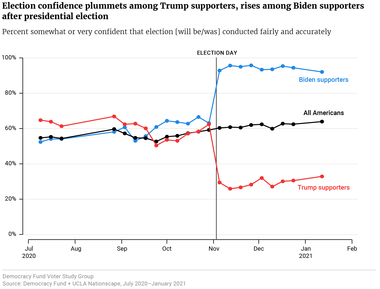

In July 2020, Nationscape began asking Americans if they felt confident that the election would be conducted fairly and accurately. At that time, a slim majority (55 percent) of Americans were somewhat or very confident that the upcoming presidential election would be conducted fairly and accurately. While Trump supporters were somewhat more likely than Biden supporters to feel confident about the fairness and accuracy of the election (65 percent vs. 52 percent), these differences were not large. By late October, overall confidence in the election had increased slightly (to 59 percent) while differences between Trump supporters (62 percent) and Biden supporters (63 percent) had evaporated.(1)

In the week after the election, the number of Americans expressing confidence in the fairness and accuracy of the election remained essentially unchanged (60 percent). However, this aggregate stability hid substantial shifts among supporters of the two major candidates. In reaction to the election’s outcome, confidence rose dramatically among Biden supporters (93 percent) while plummeting among Trump supporters (29 percent). This divide did not shrink substantially over the next two months.

(1) In the Nationscape survey, Trump supporters and Biden supporters were defined in two ways. Prior to Election Day, those who reported that they had already voted for a given candidate or that they intended to vote for that candidate were counted as that candidate’s supporters. After the election, only individuals reporting that they had voted for a given candidate were counted as supporters.

Figure 1

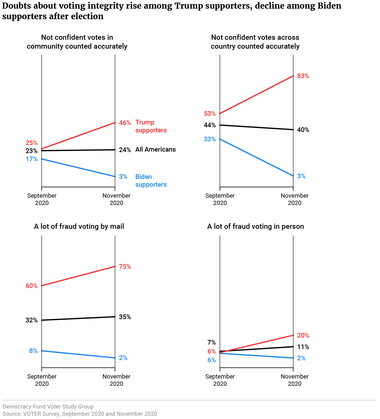

We see similar evidence of a post-election divide from the VOTER Survey. In two waves of this survey fielded before and after the election, the same set of Americans were asked four questions related to their confidence in the integrity of the vote tallying process and the prevalence of voter fraud:(2)

On all four questions, respondents became more polarized after the election. Those reporting that they voted for Trump became more likely to say they were not too confident or not at all confident that votes were counted as voters intended in their community (from 25 percent to 46 percent) or across the United States (from 53 percent to 83 percent). Additionally, Trump voters became more likely to say that there was a lot of fraud associated with voting by mail (from 60 percent to 75 percent) and voting in person (from 6 percent to 20 percent).

By contrast, those reporting that they voted for Biden became more likely to express confidence in the integrity of the election process after the election. Even though Biden voters already had lower levels of mistrust in the accuracy of vote counts, they became less likely to say they were not confident that votes were counted accurately in their community (from 17 percent to 3 percent) or across the United States (from 33 percent to 3 percent). Similarly, Biden voters became somewhat less likely to say that there was a lot of fraud associated with voting by mail (from 8 percent to 2 percent) and voting in person (from 6 percent to 2 percent).

(2) These questions are from the pre-election battery. Post-election questions were modified slightly to reflect that the election had already occurred.

Figure 2

In sum, there's ample evidence that, as in prior elections, partisan considerations in 2020 had a significant impact on the confidence voters expressed in the fairness and integrity of the election.

The question that remains is whether there was something unique about differences in voter confidence seen in 2020. In the weeks and months after the election, a sitting president and a significant portion of his party engaged in a campaign to discredit the legitimacy of the election — from gentle lies of omission to propagating wild, unsubstantiated conspiracy theories. Above and beyond the perennial partisan considerations that influence voters’ levels of confidence, did these actions create unusually high levels of distrust in the electoral process, the outcome of the election, and the legitimacy of the victor’s presidency?

Evidence presented here strongly suggests that the answer is yes.

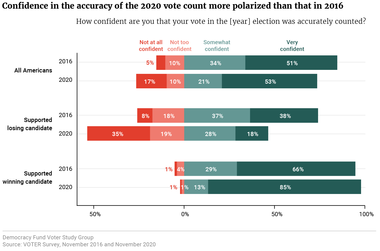

In the VOTER Survey, Americans were asked the same question after the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections: How confident were they that their own vote was counted accurately? While almost three-quarters (73 percent) of Americans said they were very or somewhat confident that their vote was counted accurately in 2020, this is lower than the 85 percent who expressed the same sentiment in 2016.

Driving this difference were highly polarized reactions by those supporting the losing candidate, Donald Trump, and the winning candidate, Joe Biden. In November 2020, more than half (54 percent) of Trump voters said they were not at all confident or not too confident that their vote had been counted accurately. This is substantially higher than the levels observed among Clinton supporters in 2016 (26 percent). In particular, the number of Trump voters who said they were not at all confident that their vote was tallied accurately was more than four times as high as the number of Clinton voters who said the same in 2016 (35 percent vs. 8 percent).

On the other hand, we also saw rising degrees of confidence among those supporting the winner in 2020. While the overall levels of confidence expressed by Biden voters in 2020 was similar to the level of confidence expressed by Trump voters in 2016 (98 percent vs. 95 percent), the number saying they were very confident in 2020 was higher than what was observed in 2016 (85 percent vs. 67 percent).

Figure 3

After the 2020 election, substantial numbers of Americans also questioned the legitimacy of Joe Biden’s victory. In the VOTER Survey, 70 percent of Americans said they would accept Joe Biden as a legitimate president, and 30 percent said they would not accept him. While Biden voters were nearly unanimous (99 percent) in their acceptance of Biden, just 34 percent of Trump voters said they would accept Biden as the legitimate president.

While not directly comparable due to methodological differences, data from Gallup suggest that this level of rejection is much higher than seen in prior elections. In both 2000 and 2016, more than eight in 10 Americans said they would accept the elected candidate as the legitimate president (83 percent for George W. Bush) and (84 percent for Donald Trump).(ii) Substantially higher numbers of Al Gore voters (68 percent) and Hillary Clinton voters (76 percent) said they would accept the winner of those elections as legitimate.

VOTER Survey respondents were also asked whether permanent harm had been done to the United States as a result of the election process. Almost six in 10 Americans (59 percent) said that permanent harm had been done while 41 percent said that no permanent harm had been done. Trump voters were far more likely than Biden voters to say that permanent harm had been done (86 percent vs. 39 percent).

Again, data from Gallup is not directly comparable but nevertheless suggests that these concerns were higher than what we saw in prior elections. Those supporting losing candidates in 2016 and 2000 were notably less likely to say that permanent harm had been done to the United States as a result of the election process (60 percent and 50 percent, respectively). It was also the case that those supporting the winning candidate in these two elections were less likely to say that permanent harm had been done (17 percent and 28 percent, respectively).

While every political race generates some degree of distrust among those whose preferred candidate has lost, the acceptance of that loss — aided by the conciliatory words and actions of losing candidates — allows our country to move forward.

Trump’s failure to abide by these conciliatory norms, and his role in actively stoking conspiracies and anger among his supporters, has left many worried that he has done significant damage to our democracy. Indeed, evidence presented above suggests that 2020 was unique in terms of the levels of distrust in the election process and doubts about the legitimacy of the incoming president.

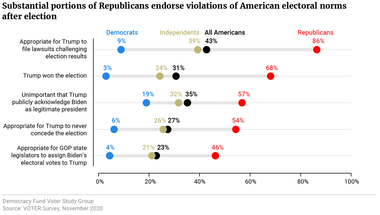

Several other questions asked in the November VOTER Survey paint a troubling picture of the post-election Republican coalition. More than eight in 10 Republicans (86 percent) thought it was appropriate for the Trump campaign to file lawsuits challenging the election’s results. About two-thirds of Republicans said that Trump actually won the election. More than half (57 percent) thought it unimportant for Trump to publicly acknowledge Biden as the legitimate president, while 54 percent said it would be appropriate if Trump never conceded.

Shockingly, 46 percent of Republicans said that it would be appropriate for Republican state legislators to try to assign electoral votes to Trump in states won by Biden — a radical violation of American electoral norms. Just 30 percent said such an action would be inappropriate, while about a quarter (23 percent) said they didn’t know if it was appropriate or inappropriate.

Figure 4

All of these data were collected prior to the January 6 attack on the Capitol building, and in retrospect, speak to the prevalence of the attitudes that motivated the events of that day.

While some thought that the attack might serve as a turning point — a shock that might finally break the conspiratorial fever that had consumed the party — it is not clear how much the event altered the attitudes of Republicans in the electorate. To be sure, multiple data sources confirm that Trump’s approval rating declined after the attack that his actions helped to incite. However, post-inaugural polling has continued to show favorable attitudes toward Trump among Republicans as well as a belief in the lies he spread about the election.

Outside of public opinion data, there also have been alarming actions taken by political elites that reflect a dedication to these election lies. Republican-controlled state legislatures have passed laws trying to make it harder to vote in 11 states — a legislative push that is directly related to conspiracies promulgated by former President Trump. The Republican party in Arizona has moved forward with a highly unorthodox review of the state’s ballots that seems determined to find evidence of fraud that didn’t happen in order to undermine public trust in November’s results. At the federal level, Republicans who have spoken out regularly against Trump’s lies, like Representative Liz Cheney, have been removed from positions of power or otherwise sidelined.

Such actions are important. The path that Republican elites forge going forward will influence how Republican voters think about the legitimacy of our current government and the integrity of our electoral system. At present, it seems likely that the country will be dealing with the conspiracies surrounding the 2020 election for the foreseeable future.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.