Democratic Norms, Ideology, Political Parties

Key Findings

In late May, as we were finishing this analysis of our public opinion survey results, American cities large and small erupted in the most intense wave of nationwide protests since the unrest that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. The trigger was once again the murder of a black man, but under very different circumstances. In this case an unarmed and nonviolent detainee, George Floyd, was asphyxiated by a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on his neck while he was already handcuffed and lying face down on the ground. Vividly documented, this evidence of police brutally snuffing out the life of one more black male pleading, “I can’t breathe,” lit a match for a large section of the nation that was fed up with systemic racial injustice, chronic police abuses, a crippling economic and health crisis, and wanton presidential insensitivity.

Within a few days, the unrest had led to over 4,000 arrests (including journalists), at least 12 deaths, widespread destruction of commercial property, and dusk-to-dawn curfews in a growing number of cities.(i) By early June, the National Guard had been summoned in half the states of the nation. And all of this came months in advance of what is expected to be one of the most polarizing and intensely contested presidential elections in modern American history, with election procedures severely stressed by the coronavirus pandemic, the rules for voting more hotly disputed than at any time in recent history, and public confidence in the process at a low. In January, before the pandemic made absentee voting a major national issue, 41 percent of Americans and two-thirds of Democrats said the country was unprepared for the November elections.(ii)

This rare convergence of crises has tested the boundaries of American presidential authority to a degree rarely seen in peacetime. In mid-April, in an attempt to gain control over the timeline for reopening states, President Donald Trump said (incorrectly) that “when somebody’s president of the United States, the authority is total.” He later walked the statement back, leaving more discretion to governors over reopening timelines. But like so many Trump trial balloons, its authoritarian vapor trails linger in the air long after popping.

As the unrest over George Floyd’s murder spread across American cities, Trump threatened to supersede the authority of governors and call in the military to quell the protests if they did not mobilize enough National Guard troops to “dominate the streets.” While he was speaking those words, police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at peaceful demonstrators in order to clear a path for the president to walk from the White House to a nearby church for a photo-op.(iii) And as it became more likely that a significant percentage of voting might take place by mail in 2020, Trump loudly complained that voting by mail would lead to fraud, adding further uncertainty to the upcoming election and raising the question of whether the election results will be broadly accepted as legitimate.

What distinguishes stable liberal democracies from their more endangered peers is not just the quality and integrity of their democratic institutions but the depth of their people’s commitment to them. Democracies are stable when citizens with diverse — and even intensely opposing — views nevertheless accept the legitimacy of their political rivals, commit to peaceful and legal means of contesting for power, and support the rules and restraints of their constitutional system. There is no clear standard for determining at what point softness or erosion in public support for these norms becomes a threat to democratic stability. But comparative research on democratic development accords with intuitive logic in suggesting that democracies will be stable when substantial majorities of the public (more than 70 percent) consistently support democracy as the best form of government, when only small minorities (less than 15 percent) are willing to endorse authoritarian options, and when very few people would consider using violence to advance their aims.(iv)

While support for democracy generally remains strong in the United States, we find that not all of these conditions for democratic stability are met. The results we report here are distinctive in several respects. The VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) methodology of repeatedly interviewing the same respondents year after year enables us to assess what few other surveys of democratic commitment are able to do: the consistency of people’s support for democracy over time. The findings we report from the last three years should sound alarm bells to at least a modest decibel.

In our panel survey, fewer than 10 percent of Americans consistently express support for authoritarian alternatives to democracy across three surveys (in 2017, 2018, and 2019). However, one-third (33 percent) of Americans have at some point in the last three years said that they think having “a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections” would be a good system of government. And about a quarter (24 percent) have said at some point that “army rule” would be a good system. Put another way, while fewer than one in 10 Americans consistently supports an authoritarian option, a third of Americans “dabble” in authoritarianism.

The December 2019 VOTER Survey goes further than we have gone in the past, and deeper than most surveys of American public opinion have ever gone, to probe the circumstances in which Americans might support an authoritarian leader’s rejection of checks on their authority. None of the scenarios we present for the president acting unilaterally without constitutional authority elicit opposition from a majority of our sample.

More disturbing still, significant percentages of voters in each party support rejection of the November election results under quite plausible scenarios, such as President Trump alleging illegal voting if he loses, or the Democratic nominee winning the popular vote but losing the general election. And those percentages take on a still more disconcerting hue when we probe the readiness of partisans to turn to violence if their party is defeated. While strong majorities of Democrats and Republicans say there would be no justification for violence, about one in five of both groups say that violence would be at least “a little” justified if the other party wins the 2020 presidential election — including about one in 10 who says that there would be “a great deal” or “a lot” of justification for violence.

This equates to tens of millions of people in a country of 225 million adults. Seen in this light, the spectacle of angry protesters, some of them heavily armed, pouring into the Michigan capitol and then later prompting the legislature to cancel its session becomes a warning sign.

While the mixed picture of support for democracy versus equivocation and skepticism is reassuring in some respects and troubling in others, viewing these numbers in the current political context presents significant cause for concern.

We are in a period of intense political polarization, with levels of political distrust and partisan enmity that rival anything we have experienced in recent memory. At the same time, the country faces its worst public health crisis in a century, its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, and widespread protests of racial injustice. All of this is unfolding in an election year in which states are scrambling to expand their capacity to handle large numbers of mailed ballots, and partisan legal funds are growing in expectation of disputes about the election process and its outcomes.

Put sharply, Americans’ commitment to the norms and institutions of democracy shows worrying signs of softness, equivocation, conditionality, or even defection at precisely the moment when our system of self-government most requires mutual restraint and unconditional support.

Put sharply, Americans’ commitment to the norms and institutions of democracy shows worrying signs of softness, equivocation, conditionality, or even defection at precisely the moment when our system of self-government most requires mutual restraint and unconditional support.

Shortly before the pandemic upended much of American life, we completed the latest round of a multi-year study of American attitudes toward democracy and authoritarian alternatives. The December 2019 VOTER Survey interviewed 5,900 Americans from November 22 to December 23, 2019. It is distinct among public polls because it draws from a longstanding panel of voters who have been interviewed periodically since December 2011, including after the 2012 and 2016 elections. Many questions about our democracy were repeated across annual surveys over the past three years. These surveys were complemented by qualitative research that included online focus groups and in-depth, hour-long interviews. (See Appendix for more on the methodology of this research.)

Our initial March 2018 report using this data, Follow the Leader: Exploring American Support for Democracy and Authoritarianism, found that only a slim majority of Americans consistently expresses a pro-democratic position across five measures of support. About three in 10 Americans said that a “strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections” or the vague alternative of “army rule” were fair or very good systems.

Further, we found the highest levels of support for authoritarian leadership come from those who are disaffected, disengaged from politics, deeply distrustful of experts, culturally conservative, and have negative attitudes toward racial minorities. Those who say it is fairly or very important for someone to have European heritage to be an American are 30 percentage points more likely to support a “strong leader” than those who decisively reject this racist conception of national identity. Those who are mistrustful of experts are 25 percentage points more likely to support a “strong leader” compared to those who are trusting of experts.(v) This is consistent with other recent scholarship showing a clear correlation between racially and culturally conservative attitudes and openness to authoritarian forms of government, raising significant challenges as America transitions to a fully multiethnic democracy.(vi)

A subsequent report in June 2018, Testing the Limits: Examining Public Support for Checks on Presidential Power, found that large majorities of Americans believe that the president should be subject to oversight and constraints on executive power. While those who have a favorable view of President Trump are much more likely to favor less accountability and oversight, we found that partisanship does not overwhelm support for democratic norms. Even among Trump supporters who are dissatisfied with democracy or open to authoritarian alternatives, many remain supportive of checks on the president’s authority.

This most recent wave of the VOTER Survey enables us to look across multiple years of survey data and clarify what Americans mean when they express support for authoritarian alternatives to democracy. We are also able to examine a wide range of scenarios to understand the conditions under which people are comfortable with unilateral action by the executive branch. Finally, we probe the conditions under which people might support physical violence to advance a political agenda or respond to the results of the 2020 election.

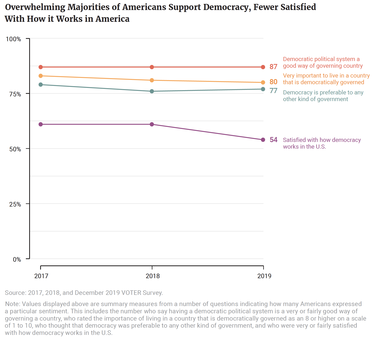

The vast majority of Americans believe in democracy. About eight in 10 (77 percent) Americans say that “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government” and even more (87 percent) say that a democratic political system is a good way of governing this country. Eighty percent of Americans also rate the importance of living in a country that is governed democratically as at least an 8 on a scale of 1 to 10. In the aggregate, these majorities have been quite stable over the past three years.

Figure 1

At the same time, Americans are relatively dissatisfied with the state of democracy in America. A slim majority (54 percent) of Americans says they are very or fairly satisfied with how democracy works in the United States. Just 11 percent say they are very satisfied. Forty-seven percent of Americans say they are not satisfied with American democracy, including 12 percent who say they are not at all satisfied. Dissatisfaction with our democracy in 2019 is eight percentage points higher than it was in 2017 and 2018 (39 percent in both years).

Historical as well as comparative data from other countries provide useful context for these numbers. According to other research, the level of democratic dissatisfaction in the U.S. has roughly doubled since 1995 — a pace of deterioration much sharper than those of most peers among advanced industrial democracies.(vii) Globally, satisfaction with our democracy puts the U.S. at only about the median of countries surveyed in recent years.(viii)

However, being dissatisfied with how democracy currently works is not the same thing as embracing an authoritarian alternative. Many Americans may be dissatisfied because of how the previous election turned out, or who is in power, not because of any inherent dissatisfaction with the idea of self-governance through regular free and fair elections.

Beyond mere dissatisfaction, we see a small but substantial number of Americans express support for authoritarian alternatives to democracy. About three-quarters (76 percent) of Americans say that a political system with a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress and elections would be a bad way of governing the country — including 54 percent who say it would be very bad. However, about a quarter (24 percent) say it would be a good way to govern the country. Similarly, while 82 percent say that army rule would be a bad way of governing the country, 18 percent think it would be a good way of governing.

Across our three surveys covering three years, attitudes about a strong leader and army rule have not changed. In aggregate, the overall number of Americans who view these systems as good or bad ways of governing has shifted only a single point.

The overall stability of these attitudes masks a fair amount of inconsistency among individuals over this period. More than a quarter (26 percent) of those interviewed in 2017 have changed their mind on whether or not a strong leader is a good way to govern the country. About one in five (18 percent) Americans has changed their mind on the value of military rule.(1) However, since the individual level changes have been equal in both directions, they have canceled each other out.

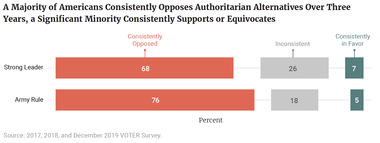

Overall, about three-quarters (76 percent) of Americans have been consistently opposed to army rule and about two-thirds (68 percent) have been consistently opposed to a strong leader. By contrast, just 5 percent have been consistently in favor of army rule, and just 7 percent have consistently expressed a preference for a strong leader.

It is reassuring to recognize that most Americans consistently oppose authoritarian forms of government and only a small percentage consistently favor them. Nevertheless, a surprisingly high percentage of the electorate appears to be unsure — open to an undemocratic alternative one year, opposed to it the next.

(1) Changing one’s mind here is interpreted as moving from a positive view of an authoritarian option (very or fairly good) to a negative view (very or fairly bad), or vice versa. We do not count changes in degree of good or bad.

Figure 2

Is support for authoritarian alternatives getting better or worse? The data are mixed.

In 2017, we found that American support for a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections had significantly declined since the 2011 World Values Survey.(ix) In fact, it was below what the World Values Survey found in 1999 (29 percent), 2006 (32 percent), and 2011 (34 percent), but equal to the level in 1995 (24 percent). The proportion of Americans supporting a strong leader has been stable across the 2017 (24 percent), 2018 (23 percent), and December 2019 (24 percent) waves of the VOTER Survey.

Support for army rule, on the other hand, has been increasing over time. In 1995, only 6 percent of World Values Survey respondents expressed support for army rule. This increased to 9 percent in 1999, 14 percent in 2006, and 17 percent in 2011 — closely matching the levels that we found in the last three years of the VOTER Survey.

How seriously should we take those who say they support authoritarian alternatives to democracy? Though the aggregate number of Americans supporting these alternatives has remained quite consistent, a significant number of people have changed their responses over a three-year period. Does this suggest that people do not mean what they are saying? Or could it be that the data is unreliable because the questions are worded in a way that is confusing or misleading?

In 2017, 2018, and 2019, the VOTER Survey repeated questions that have been asked for about 25 years in the U.S. and around the world through the World Values Survey to assess support for authoritarian alternatives to democracy. However, imprecision in two of these standard public opinion measures is significant enough to raise questions about the degree to which they accurately assess what the public really thinks. Would a more detailed version of questions about army rule and a strong leader generate a more accurate level of support?

Online focus groups that we observed in 2018 suggest that Americans have little context for the idea of military rule.(2) In response we developed a new question that provides more detail about what the military could do as well as why they might do it:

In some countries, military leaders have suspended elections, closed down the legislature, and temporarily taken charge of the government in order to address extreme corruption. What would be your view if the military took these steps in the United States?(3)

We hypothesized that with this more explicit language — signaling a temporary military dictatorship in the United States — a substantial portion of the 18 percent supporting “army rule” would respond differently. Instead, 13 percent somewhat or strongly favor the scenario with only 69 percent somewhat or strongly opposing it. This result is largely consistent with a recent report by Elizabeth Zechmeister, which finds that American support for a coup in the United States was only modestly influenced by clarifying that the coup would involve removal of the president by force.(x)

Notably, an additional 18 percent said they “don’t know” if they favor the military suspending elections, closing down the legislature, and taking charge of the government. This “don’t know” option was not available on the original version of the question, so we cannot make an apples-to-apples comparison between the two. It is possible that without this option some or all of these respondents would have expressed support for army rule, which makes the small drop in support between the two questions even more surprising.

As with repeating a question over time, changing the language of a question also produces inconsistent responses. While 82 percent of Americans say army rule is bad and 69 percent reject the new, more explicit scenario, only 64 percent reject both. Twelve percent of Americans support one, but not the other. Another 11 percent reject army rule in the abstract but aren’t so sure about the more specific scenario. Another 7 percent support army rule in the abstract but are less certain about the specific scenario. Finally, just 6 percent support

army rule on both questions.

(2) See Appendix for more information on this qualitative research.

(3) Response options were strongly favor, somewhat favor, somewhat oppose, strongly oppose, or don’t know.

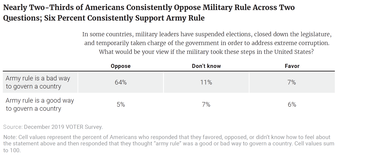

Table 1

The good news here is that nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of Americans are consistently opposed to army rule and only 6 percent consistently support it. However, the inconsistencies suggest many people haven’t thought all that deeply about the possibility. While hardcore support for army rule may not be as deep as any topline result suggests, neither is opposition to it. As is the case with much data on public attitudes about democratic alternatives, we are left with a concern about the degree to which some may be open to actions inconsistent with democratic norms and values.

Another World Values Survey question that we used asks about the favorability of a “strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress and elections.” This question is also potentially confusing because it doesn’t distinguish between support for a more illiberal democracy with a weak legislative branch and support for a system that does away with electoral democracy altogether. To discern whether this bundling of the two concepts is creating a misleading response, we created a “split sample” question in a 2018 YouGov survey that breaks the inquiry up into its component parts.(4) Those surveyed gave response to one of three variations on “a strong leader” system:

Here are various types of political systems. For each one, would you say it is a very good, fairly good, fairly bad, or very bad way of governing this country?

1. Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections

2. Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress

3. Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with elections

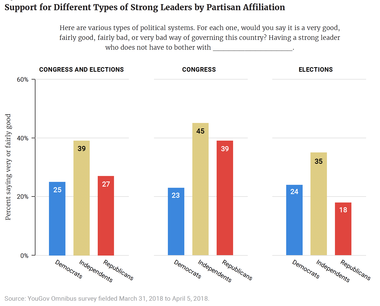

Support for the first variation — a strong leader without Congress and elections — was higher than in our other surveys at 29 percent. Support for a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress (33 percent) and one who doesn’t have to bother with elections (24 percent) were only somewhat different from support for a leader who doesn’t have to bother with both. However, the difference between support for a leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress and one who doesn’t have to bother with elections was statistically significant.

The higher support for strongman rule when we focus the question on Congress alone was largely driven by Republicans and independents. Eighteen percent of Republicans and 35 percent of independents wanted to bypass elections, but 39 percent of Republicans and 45 percent of independents wanted to bypass Congress. These numbers are all the more notable given that we asked this question in 2018 when Republicans controlled both the United States Senate and the House of Representatives.

Notably, Democrats were relatively consistent in their support — being just about as likely to support a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with elections (24 percent), Congress (23 percent), or both (25 percent).

(4) This survey was fielded between March 31, 2018, and April 5, 2018 among 2,000 respondents on YouGov’s weekly omnibus.

Figure 3

It appears that the original wording of the strong leader question does mask some difference of opinion related to the conditions under which the public would support a strong leader. Breaking up the question demonstrates that — from a public opinion perspective — an illiberal democracy with weaker checks on executive authority may be a greater threat to be concerned about than an overt attempt to do away with elections. That said, public support for a strong leader remains relatively high under both scenarios.

Another potential critique of the reliability of responses to these questions about support for alternatives to democracy is whether participants are providing flip answers and do not feel strongly about their survey responses. Do they really mean what they say? To test this concern, we employ follow-up questions that ask how strongly participants feel about some of their responses to questions about the importance of democracy. For example, after asking whether democracy is preferable to any other kind of government, we ask whether respondents feel “strongly” or “not so strongly” about their answers.

For the past three years, we have asked participants which of the following statements is closest to their point of view:

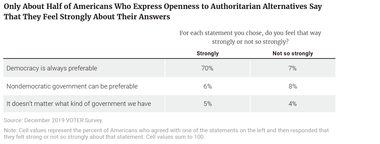

More than three-quarters (77 percent) say that democracy is preferable while just 14 percent say that nondemocratic government can be preferable in some circumstances. An additional 9 percent say that it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.

When it comes to the strength of these attitudes, people generally feel strongly about democracy and have weaker opinions even when they expressed support for those other statements. Out of the 77 percent of Americans who think that democracy is preferable, the overwhelming majority (70 percent) say they hold this view strongly. Far fewer Americans hold this view weakly (7 percent).

Table 2

By contrast, those who offer support for alternatives to democracy express much less certainty about their responses. Just 6 percent of Americans feel strongly about nondemocratic government being preferable in some circumstances while 8 percent say they don’t feel very strongly about this attitude. Similarly, roughly equal numbers of Americans say they feel strongly (5 percent) and not so strongly (4 percent) about the kind of government not mattering for someone like them.

Again, supporters of democracy should be encouraged that those who say democracy is always preferable feel strongly about that preference. Only 6 percent of Americans feel strongly that a nondemocratic government can be preferable — a proportion comparable to those that consistently favor a strong leader or army rule. While there do appear to be some consistent authoritarians, the bigger concern appears to be the larger number who dabble in tolerance for authoritarian options.

Public emergencies often call for the appropriate use of emergency powers to protect the health and safety of the public. This decisive use of public powers and resources can conflict with constitutional protections of civil liberties and limits on unilateral power. In Hungary, for example, the country’s leaders quickly seized upon the current pandemic to enact a broad series of laws enabling Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to govern by decree without having to be concerned with the legislature or elections.(xi) History is full of democratic leaders claiming “temporary” emergency powers that they never relinquish.

As the United States navigates its own public emergency, it is useful to revisit public support for checks and balances.

As we noted earlier in this report, most Americans express strong support for living in a democracy. Further, most Americans favor important aspects of a liberal democracy, like the rule of law and checks and balances.

Far more Americans say that the president must always obey laws and the courts, even if he thinks they are wrong (87 percent) than say that the president should not be bound by these institutions (13 percent). There are far more who are supportive of the news media scrutinizing the president and other politicians to ensure they are accountable to the American public (77 percent) than there are those who say that these leaders should be able to make decisions without being constantly monitored (23 percent). There are far more Americans supportive of Congress providing oversight of the president and executive branch (77 percent) than those who say that Congress should give the president freedom to make decisions that he feels are right for the country. An overwhelming majority agree that citizens should always be free to publicly criticize the president, even when the country is at war (77 percent).

On the surface, these numbers are reassuring. But how much substance is there behind these answers? While we may all like to believe that they represent deep commitments to elements of liberal democracy, it is worth testing whether support slips away when Americans confront real-world scenarios that authoritarians often use to erode democracy, and when partisan loyalty conflicts with professed values.

In the December 2019 VOTER Survey, we tested several rationales for unilateral executive branch actions that have commonly been used by authoritarians in the past. Under each scenario we asked a random half of our sample how appropriate it would be for a Democratic or Republican president to take action on their own, even if the Constitution does not give them the explicit power to act without congressional approval. We tested the following justifications for unilateral action:

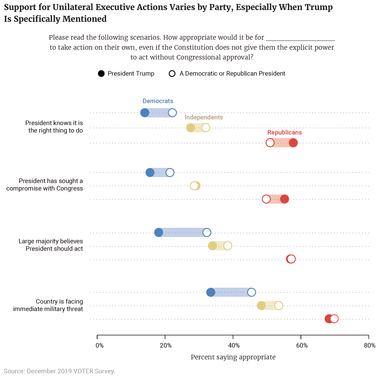

Unilateral action by the president is seen as appropriate by a majority (54 percent) in the face of an immediate military threat, which is unsurprising given Congress’ delegation of war powers over the past few decades. However, 41 percent of people also say unilateral action would be appropriate if a large majority of the American people believe that the president should act. About one-third (34 percent) say such action would be appropriate if the president knows it is the right thing to do for the American people or if the president has sought a compromise with Congress and the opposition party is playing partisan games (32 percent).

What is perhaps most troubling is how few Americans think any of these scenarios are “very inappropriate.” Fewer than three in 10 (28 percent) think unilateral executive action is very inappropriate if the president knows it is the right thing to do, if the president has sought compromise with Congress but the opposition party is playing partisan games (25 percent), or if a large majority of American people believe the president should act (21 percent).

These responses vary by partisanship. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say unilateral executive action is appropriate during a military threat (70 percent vs. 45 percent), when backed by a large majority of Americans (57 percent vs. 32 percent), when the president knows it is the right thing to do (51 percent vs. 22 percent), and when the president has already sought compromise with Congress but the opposition party is playing partisan games (50 percent vs. 21 percent).

However, this question specifically asks respondents about a “Democratic or Republican president” — a scenario that somewhat intentionally makes them think about what unilateral executive action might look like under a president who doesn’t share their partisanship. To test how people might react to a co-partisan in the White House, we asked the other random half of respondents the same set of questions but replaced “Democratic or Republican president” with “President Trump.” This alternative wording widens the gaps between Democrats and Republicans.

For example, Democrats are less likely to consider unilateral executive action appropriate during an immediate military threat when the question names President Trump specifically (33 percent say it’s appropriate ) than when the question names a “Democratic or Republican president” (45 percent of Democrats say it is appropriate when Trump is not mentioned). Similarly, the mention of Trump’s name as compared to a generic Democratic or Republican president lessens support for presidential action when backed by a large majority of Americans (18 percent vs. 32 percent), when the president knows it is the right thing to do for the American people (14 percent vs. 22 percent), and when the president has sought a compromise with Congress but the other party is playing partisan games (16 percent vs. 21 percent).

By contrast, Republicans are slightly more supportive of unilateral executive action when Trump is specifically mentioned compared to a nameless “Democratic or Republican president.” They are more likely to say it’s appropriate for the president to act when he knows it is the right thing to do (58 percent vs. 51 percent) and when the president has sought a compromise with Congress but the other party is playing partisan games (55 percent vs. 50 percent). On the other two questions, the difference is negligible.

Figure 4

For each question, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to support unilateral action, even in the generic “Democratic or Republican president” condition. This gap widens significantly when President Trump is specifically mentioned, mostly because Democrats become much less supportive upon associating the actions with Trump.

In short, Republicans are both more supportive of a “strong leader” in the abstract, and slightly more supportive of President Trump taking unilateral actions. This indicates that support for authoritarian leadership is influenced by partisanship. When Americans are asked a question about specific unilateral executive actions, they likely call to mind a particular leader taking those actions. The more they support that leader, it appears, the more likely they are to support those actions. Similarly, the more they distrust that leader, the more they are likely to oppose those actions. Abstract values about democratic norms are important, but when they come into confrontation with partisan loyalty or confidence in a specific leader, those values soften. And consistent with much of history, a military threat is the condition most likely to lead citizens to support authoritarian leadership.

Examining responses to instances of executive branch abuses of power is another way to test how deep public support for democratic norms runs. Specifically, the public’s response to the recent impeachment inquiry into President Trump’s withholding of military aid to Ukraine raises profound questions about the ability of Congress to hold the president accountable to the rule of law.

The December 2019 VOTER Survey was conducted while the House impeachment investigation of President Trump was well underway. In the survey, we asked whether respondents thought several of President Trump’s actions that were being investigated had actually taken place. More importantly, we asked how serious it would be if those actions had actually happened. The degree to which Americans believe that a given action is serious should, in principle, line up with their abstract support for the rule of law and of congressional oversight over the executive branch.

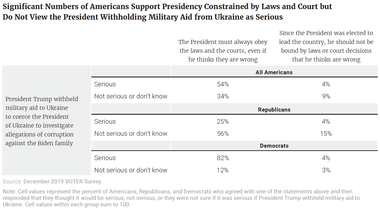

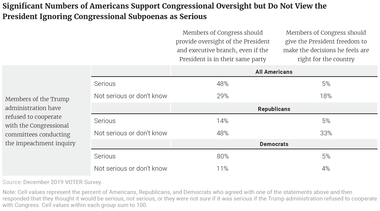

Overall, a majority (58 percent) of Americans thought it would be serious if the president withheld military aid to Ukraine to coerce the president of Ukraine to investigate allegations of corruption against the Biden family. A majority thought it would be serious even if President Trump had just urged the president of Ukraine to investigate allegations of corruption against the Biden family (53 percent). Additionally, a majority of Americans thought it would be serious if members of the Trump administration refused to cooperate with the congressional committees conducting the impeachment inquiry (53 percent).

It is worth looking at how these responses relate to the public’s professed strong support for the rule of law and congressional oversight. To understand this better, we break down our survey participants based on their response to the question at the heart of the impeachment inquiry: whether Trump withheld military aid.

A majority (54 percent) of Americans held the view that the president must obey the laws and courts and also said that withholding aid would be serious if true. However, about a third (34 percent) of Americans said that it is important for the president to obey the law but also said that withholding aid would not be serious if true or that they were uncertain whether it was serious.

Table 3

Partisanship explains most of this incongruity. Among Republicans, just a quarter (25 percent) said the president must always obey the laws and the courts and that withholding aid would be serious if true. By contrast, an overwhelming majority (82 percent) of Democrats held both of those beliefs.

A majority (56 percent) of Republicans held the somewhat contradictory view that presidents must always obey the laws and the courts, but also said that withholding aid would not be serious if true or said they don’t know if it would be serious.

A similar pattern occurs in response to congressional oversight. Separately, respondents were asked whether members of Congress should provide oversight of the president and executive branch and whether it would be serious if members of the Trump administration refused to cooperate with the congressional committees conducting the impeachment inquiry.

Here the inconsistencies seem even starker, since the question is essentially the same. Almost one in three (29 percent) Americans simultaneously say that Congress should provide oversight yet does not believe the president ignoring congressional subpoenas was a serious problem.

Table 4

Again, partisanship explains much of the story. A remarkable 48 percent of Republicans simultaneously say that members of Congress should provide oversight and that it was not serious or they don’t know if it was serious if the Trump administration refused to cooperate with Congress.

These partisan incongruities are consistent with recent work that shows that partisan loyalty overrides fealty to democratic norms.(xii) They are a reminder that responses to abstract questions about support for democracy can be misleading, especially in a highly polarized environment.

On May 1, as the COVID-19 pandemic was reaching a fever pitch of biological spread and political controversy in the United States, hundreds of angry protestors — some of them armed and dressed in military uniforms — converged on the Michigan state capitol to protest Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s extension of her stay-at home order. In an iconic photograph, some of the protestors who were admitted into the building can be seen screaming at police standing guard in surgical masks. A few of the protestors openly carried guns into the State Senate gallery, which is not illegal in Michigan. While there were no arrests or injuries, many observers and at least a good number of Michigan legislators felt a cardinal principle of democratic restraint and civility had been breached. The BBC News reported that “One state senator said several of her colleagues wore bulletproof vests.”(xiii) Two weeks later, the state closed down the state capitol building and “canceled its legislative session rather than face the possibility of an armed protest and death threats against Governor Gretchen Whitmer.”(xiv)

Shocking though the display of weaponry was, with its clear intent to intimidate, it would soon become a mere footnote to the eruption of nationwide protests and actual violence that followed the May 25 Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd. Beyond the explosion of understandable public anger over institutionalized racism and police violence, and the fresh incidents of police overreaction and brutality, the crisis also surfaced allegations that anarchists and other shadowy extremist groups on the far left and far right were exploiting public outrage in order to instigate acts of violence and destruction. With public anger, fear, polarization, and distrust rubbed raw, it is important to consider the potential for a new outbreak of violence in response to a major dispute over the 2020 election outcome.

Most indications suggest that the public has been paying close attention to the 2020 election. The campaign will be intensely fought and the results may be close. As was the case in 2016, it is possible that we may see a divergence between the outcome of the popular vote and the Electoral College. Undoubtedly, we will see significant disputes about perceived or actual attempts to manipulate the outcome by foreign and domestic actors. Further, in the new context of the coronavirus pandemic, we face the prospect of serious controversies about how the elections will be administered and whether every voter who wishes to cast a mail ballot will be able to do so. The high stakes of a polarized presidential election, and the absence of consensus on the rules of the game, portend potentially severe challenges to the legitimacy of the election outcome.

In the current political environment, accusations by either candidate that the results of a presidential election are not legitimate could quickly pull the country into highly charged conflict that could seriously undermine our democracy. If partisans already do not trust the intentions of leaders from the other party and have low trust in our institutions of government how will they respond if their preferred candidate says that the election results are not legitimate?

The December 2019 VOTER Survey included questions on three scenarios to help understand how the public may respond if the 2020 election’s results are called into question. Testing hypothetical scenarios like these has its limits, since much will likely depend on how leaders respond and other specific details that are hard to capture in a short, static question. At the very least, these scenarios do reveal the extent to which a candidate making these kinds of challenges will find a large receptive audience. In other words, we believe they highlight the potential for a national crisis if the circumstances of the vote or the choices of a national party leader call the legitimacy of the election into question.

Respondents were asked how appropriate the following actions would be:

If there is truly credible evidence of massive voter fraud or voter interference, calls by public officials for some legal remedy would be appropriate. However, there is ample historical precedent for candidates to mislead the public about potential election interference in order to rally supporters against an electoral outcome with limited or no evidence. While these scenarios are silent on the question of whether or not there is evidence for the alleged interference, they provide some sense for how the public could respond.

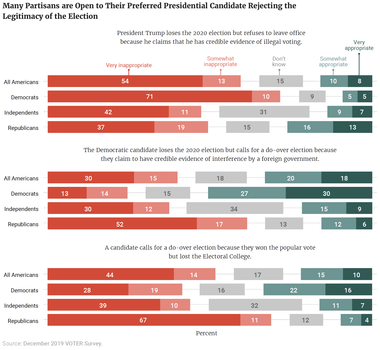

Our data shows that partisans are quite open to their preferred presidential candidate rejecting the legitimacy of the election if they claim credible evidence of illegal voting or foreign interference. About three in 10 (29 percent) Republicans say it would be appropriate for President Trump to refuse to leave office because he claims that he has credible evidence of illegal voting. An additional 15 percent of Republicans say they “do not know” if it would be appropriate for him to refuse to leave office. This is compared to 10 percent of Democrats who say it would be appropriate and 9 percent who say they don’t know.

Figure 5

On the other hand, 57 percent of Democrats say that it would be appropriate for a Democratic candidate to call for a do-over election because they claim to have credible evidence of interference by a foreign government. An additional 15 percent of Democrats say they do not know if it would be appropriate. This is compared to only 18 percent of Republicans who say it would be appropriate and 13 percent who say they do not know if it would be appropriate.

Further, 38 percent of Democrats say it would be appropriate for a candidate to call for a do-over if they win the popular vote but lose the Electoral College. An additional 16 percent of Democrats say they do not know if it would be appropriate. This is compared to only 11 percent of Republicans who say it would be appropriate and 12 percent who don’t know.

Obviously, the potential circumstances of any post-election challenge will depend on many contingencies, such as the closeness of the election, the credibility of the allegations, and perhaps most importantly, the extent to which such challenges are supported by partisan and media elites. These numbers don’t predict what will happen. What they tell us is that a significant share of partisans are open to the idea of a do-over.

If a significant share of the population may question the legitimacy of the election, we must immediately consider the potential repercussions. To what extent should we be concerned about the threat of political violence by more than a few fringe actors, especially in an environment in which substantial numbers of partisans distrust the legitimacy of election results?

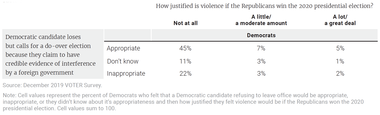

In a recent post, Most Americans Reject Partisan Violence, But There Is Still Cause for Concern, Nathan Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason analyze Voter Study Group data from the same December 2019 VOTER Survey on which this report is based about attitudes towards political violence. Specifically, Democrats were asked the following questions (and Republicans were asked the same questions with the partisan labels switched):

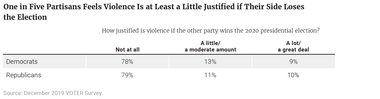

According to Kalmoe and Mason, overwhelming majorities of Americans completely reject partisan threats and violence. However, a “small but substantial minority indicates some openness to partisan threats and violence across these measures.” About one in five partisans (people who describe themselves as Democrats or Republicans) says that violence would be at least “a little” justified if the other party won the 2020 presidential election. About one in 10 of both Democrats (9 percent) and Republicans (10 percent) say that if their party were to be defeated there would be “a lot” or a “great deal” of justification for violence.

Table 5

Kalmoe and Mason put these numbers into important context:

“These relatively small percentages of respondents who endorse partisan threats and violence theoretically represent tens of millions of Americans. However, violent views do not mean these people are likely to behave violently. The vast, vast majority will not, despite their views, because of the norms and laws proscribing violence. We still worry, however, because these Americans may still engage in lower-level aggressive behaviors that contribute to a broader environment encouraging violence by others.”

How do these attitudes toward partisan motivated violence compare to Americans’ attitudes about the appropriateness of presidential candidates questioning the legitimacy of election outcomes?

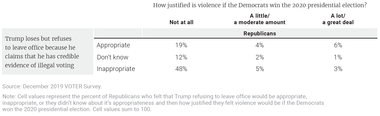

Among Republicans, most of those who think it might be appropriate for President Trump to refuse to leave office also say violence would not be justified. About one in five (19 percent) Republicans says it would be appropriate for Trump to refuse to leave office if he claims that he has credible evidence of illegal voting but also say violence is not at all justified. An additional 12 percent say they don’t know if Trump’s actions under that scenario would be appropriate and also reject violence.

However, 13 percent of Republicans simultaneously say Trump refusing to leave office would be appropriate or that they are uncertain about its appropriateness and also say that violence would be at least a little justified if Democrats won the 2020 election.

Table 6

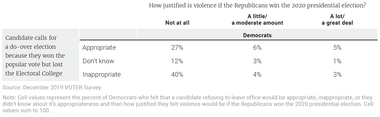

Among Democrats, the other two scenarios — foreign intervention and the Electoral College supporting the popular vote loser — are pertinent. Most Democrats who think it might be appropriate for a candidate to call for a do-over election because of a mismatch between the popular vote and Electoral College outcomes do not believe that violence would be justified if Trump were to win the 2020 election. About a quarter (27 percent) of Democrats say a call for a do-over would be appropriate but do not endorse violence at all. An additional 12 percent say they don’t know about the appropriateness of a call for a do-over election and also reject violence.

However, 15 percent of Democrats simultaneously say a Democratic candidate calling for a do-over election would be appropriate or that they are uncertain about its appropriateness and also say that violence would be at least a little justified if a Republican won the 2020 election.

Table 7

There is a similar pattern on the question of foreign interference. Most Democrats who think it might be appropriate for a candidate to call for a do-over election because of interference by a foreign government do not believe that violence would be justified if Trump were to win the 2020 election. Almost half (45 percent) of Democrats say a call for a do-over would be appropriate but do not endorse violence at all. An additional 11 percent say they don’t know about the appropriateness of a call for a do-over election and also reject violence.

However, 16 percent of Democrats simultaneously say a Democratic candidate calling for a do-over election in the face of foreign interference would be appropriate or that they are uncertain about its appropriateness and also say that violence would be at least a little justified if a Republican won the 2020 election.

Table 8

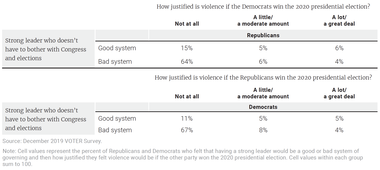

Finally, we can examine the connection between openness to electoral violence and support for a strong leader. Among both Democrats and Republicans, a similar picture emerges. Those who believe a strong leader is a good system of government are more likely than those who believe it is a bad system to say that violence after the electoral win of a political opponent is justified. About one in 10 Republicans (11 percent) and Democrats (10 percent) endorse a strong leader style of government and believe that violence might be justified after an election in which the opposing party wins.

Table 9

Across both Democrats and Republicans, we find a small but still significant 5 percent of partisans who are both receptive to a call for a do-over election and believe a lot or a great deal of violence would be justified if their preferred party loses. Similarly, we find about 5 percent who support a “strong leader” and think electoral violence is justified.

Whether or not this will translate into actual action is obviously impossible to say at this point. But again, in a nation with well over 200 million adults, even a small percentage taking to the streets in violent protests would represent a significant disruption and challenge to the continued stability of American democracy.

The story that emerges from this analysis raises both promise and the prospect of peril.

Despite our division, distrust, and dysfunction, most Americans continue to believe in and support our democracy. Over three years of research, we consistently find that more than three-quarters of Americans say that democracy is preferable to any other kind of government, and nearly nine in 10 say that democracy is a good way to govern this country. Moreover, only a very small portion of the American public is consistent in its support for authoritarian alternatives to democracy (roughly 5 percent) or enthusiastic about political violence (roughly 10 percent). Most of those who do express support for these things tend to be inconsistent and report not feeling strongly about their answers to these questions.

Regardless of how we cut the data, we find the percentage of Americans who have clearly aligned against democracy to be in the single digits. And while it can be disconcerting to see that a quarter of Americans in any given survey express support for a strong leader who doesn’t have to worry about Congress and elections, this is nothing new and is in fact lower than most similar surveys over the past twenty-five years. All of this is encouraging news.

The peril emerges when we probe below abstract principles by asking about more specific scenarios and pitting partisan fealty against what most of us know to be the “right” answers about the importance of democracy.

We are several months away from a presidential election that could be very close. Both sides see loss as an existential threat and, whether or not any actual fraud or interference takes place, a substantial portion of the public may be predisposed to believe the kinds of misinformation and conspiracy theories that continue to circulate, especially if they come from trusted political and media elites.

Further, COVID-19 has created a public emergency where voting processes are undergoing changes to ensure everyone can vote, and yet sharp partisan divisions have emerged over what might have been expected to be purely administrative issues, such as expanding absentee voting. Add to this the new partisan tensions over how fast to open the economy — and even whether people should wear facemasks in public — and new layers of partisan division and distrust pile up atop the old ones.

In such an environment, we see considerable kindling that could flare up around the election, given the right spark.

About a quarter to a third of Americans flirt with the idea that an alternative to democracy would be a good thing. When we push them by asking questions in a different way to reduce confusion, the numbers do not change significantly. When facing real-life threats to democratic norms, many of those who profess support for things like congressional oversight begin to question the seriousness of ignoring a congressional subpoena. A surprisingly high percentage of Americans are willing to disregard checks on executive authority when “the president knows it is the right thing to do for the American people.” Perhaps most concerning is that one in five partisans can see some justification in political violence if the other side wins the presidential election. And a sizable portion of both parties appears primed to accept a claim by their candidate that the election’s results were not legitimate.

In short, within a significant portion of the American public, professed support for democracy appears somewhat superficial and may be easily swept aside by partisan allegiance, outrage over the election results, or frustration with a corrupt or rigged political process.

At a time when our political system faces deep and pervasive threats, we should not count on public support for our democracy as a bulwark. Much will depend on preparation, leadership, and a bit of luck that the worst-case scenarios — such as a too-close-to call election that triggers widespread claims of fraud, suppression, or interference, with no clear way to name a winner — do not come to pass.

Online Panels

Following the July 2017 VOTER Survey — which featured a variety of questions about American attitudes toward democracy and authoritarian alternatives — participants in the survey were contacted again to participate in online discussions. Three multi-day discussions were held with participants split into three groups based on their initial responses to the VOTER Survey as well as a series of screening questions: Those who had given responses that were very supportive of authoritarian alternatives (including six participants engaged March 5-8, 2018), those who gave responses that were somewhat supportive of authoritarian alternatives (including nine participants engaged March 4-7, 2018), and those who gave responses supportive of democracy (including 11 participants engaged March 3-6, 2018). Edge Research was responsible for both the recruitment of participants from the pool of VOTER Survey respondents as well as conducting the online discussions.

One-on-one Interviews

In June 2018, a series of one-on-one interviews were conducted in Greenville, South Carolina (June 6-7) and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (June 11-12). In each location, 12 onehour interviews were conducted. Six of the interview subjects were survey participants who expressed support for authoritarian alternatives and anti-democratic attitudes, and the other six interview subjects were survey participants who expressed support for democracy and democratic attitudes. Edge Research was responsible for both the recruitment of participants as well as conducting the one-on-one interviews.

Topics

In both cases, conversations were structured to try and answer the following questions:

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.