Democratic Norms, Executive Branch, Global Politics

Key Findings

Last year, special counsel Robert Mueller was appointed to investigate Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, including any links or coordination between Russia and the campaign of Donald Trump. To date, this investigation has resulted in over 100 charges against 14 Russians, six Americans, and three companies.

A fierce battle has raged since the early days of the investigation to shape and influence public perceptions about the investigators and their potential findings. The outcome of these efforts may have longstanding repercussions for the nation’s core democratic norms and institutions.(i)

This Voter Study Group Brief focuses on several dimensions of how the public currently perceives the investigation, including its fairness and integrity, the seriousness of the allegations, and the appropriateness of actions that the President could take to curtail the investigation. It is based on the April–May 2018 VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) of 6,005 Americans, which included a battery of questions about the special counsel’s investigation.(1)

(1)The survey firm YouGov interviewed 6,005 Americans between April 5 and May 14, 2018. Among this group, 4,705 were reinterviewed from a longitudinal panel that has been surveyed several times since 2011. Additionally, YouGov recruited a fresh cross-section of 800 millennials (18–24 years of age) and 500 Hispanics to facilitate the analysis of those sub-groups. The entire sample has been weighted to benchmarks for the American adult population as a whole.

Over the past several weeks, President Trump has repeatedly called the Russia investigation a partisan “witch hunt” in a series of increasingly pointed tweets. At the same time, Congressman Devin Nunes has led a contingent of Republicans in Congress in aggressively questioning the motivations of the Justice Department and the integrity of the investigation.

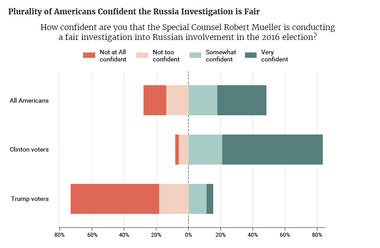

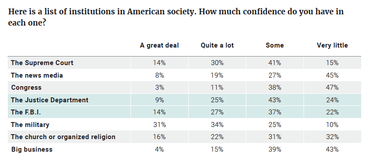

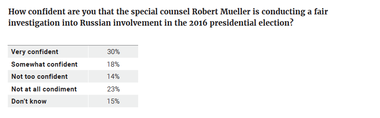

In this context, nearly half (48 percent) of Americans say that they are “confident” that the special counsel, Robert Mueller, is conducting a fair investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election, including 30 percent who are “very confident” and 18 percent who are “somewhat confident.” More than one-third (36 percent) are skeptical — saying they are “not too” or “not at all confident” in the investigation — while 15 percent say they “don’t know.”

Views on the investigation’s credibility are deeply divided along partisan lines. An overwhelming majority of Clinton voters say they are “very confident” (62 percent) or “somewhat confident” (21 percent) that the investigation is being conducted fairly. Only 15 percent of Trump voters say the same. In contrast, most of those who voted for Trump in 2016 are either “not too confident” (18 percent) or “not at all confident” (54 percent) in the fairness of the investigation.(2)

Figure 1

(2) Within the panel sample, 50 percent of respondents reported voting for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 wave, while 43 percent reported voting for Donald Trump. In the full 2018 sample, including 18–24-year-olds and the Hispanic oversample — 21 percent of respondents said they “strongly approve” of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as President, 19 percent “somewhat approve,” 10 percent “somewhat disapprove,” 46 percent “strongly disapprove,” and 4 percent “don’t know.”

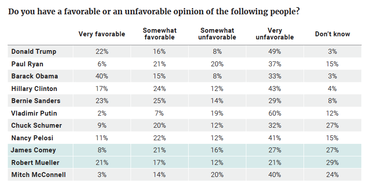

Every facet of the investigation — from prominent figures to government institutions — reveals a partisan divide. Trump voters are more likely than Clinton voters to have an unfavorable view of special counsel Robert Mueller (66 percent vs. 9 percent) and former F.B.I. Director James Comey (75 percent vs. 27 percent). Trump voters are also less likely to express confidence in the Justice Department (22 percent vs. 43 percent) and the F.B.I. (21 percent vs. 58 percent).

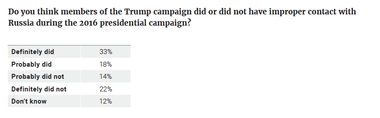

Beliefs about whether improper contact occurred between members of the Trump campaign and Russia are similarly polarized. While a majority (51 percent) of Americans believe that improper contact occurred, partisan reactions are almost mirror opposites of one another. Ninety percent of Clinton voters believe that improper contact “likely occurred” while 82 percent of Trump voters say it “likely did not.”

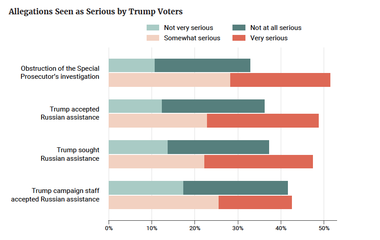

While most Republicans are highly skeptical about the Russia investigation, the overwhelming majority of Americans, including Trump supporters, believe that the allegations being investigated are serious. This may suggest that public opinion could shift despite partisan divisions if overwhelming findings of wrongdoing emerge — especially if findings are persuasive to key Republican political and media leaders. But there is certainly no guarantee that such a shift would occur, as there are likely to be significant partisan differences in interpreting any eventual findings of the investigation.

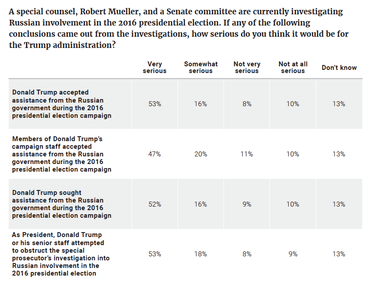

Respondents were asked how serious the following allegations would be if they were found to be true:

In each case, a consistent and strong majority of Americans say the allegations would be “very” or “somewhat serious.” Around two-thirds say each of the four actions would be “very” or “somewhat serious” while about one in five say they would be “not very” or “not at all serious.” For each, 13 percent say they “don’t know” how serious it would be.(3)

Even among Trump voters, a plurality saw each of the allegations as serious. Fifty-one percent of Trump voters said obstruction of justice would be “serious,” compared to 33 percent who said it “wouldn’t be.” Forty-nine percent of Trump voters said it would be “serious” if Trump had accepted Russian assistance and 47 percent said it would be “serious” if Trump had sought assistance, compared to 36 percent and 37 percent, respectively, who disagreed. There was also considerable uncertainty about the seriousness of the allegations with about one in six Trump voters saying they “did not know” if the allegation was serious or not.

(3)See Appendix for full results.

Figure 2

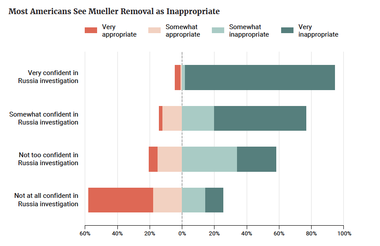

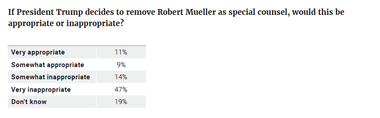

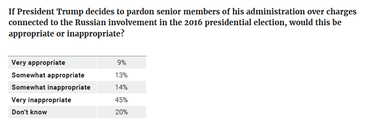

Most Americans think it would be inappropriate for President Trump to intervene in the Russia investigation. A majority say it would be “very” or “somewhat inappropriate” for the president to remove Robert Mueller as special counsel for the Russia investigation (60 percent) or pardon senior members of his administration over charges connected to Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election (59 percent). Only about one in five Americans see these interventions as “appropriate” (20 percent and 22 percent, respectively) while a similarly-sized portion are uncertain about their appropriateness (19 percent and 20 percent, respectively).

There is a substantial division between those who are confident the Russia investigation is being conducted fairly and those who are not. A majority — if not an overwhelming majority — of those who feel “very confident,” “somewhat confident,” or “not too confident” in the fairness of the Russia investigation say that it would be “inappropriate” for the president to remove Mueller as special counsel (94 percent, 76 percent, and 58 percent, respectively). It is only among those who say they are “not at all confident” in the fairness of the investigation that a majority (58 percent) thinks it would be “appropriate” to remove Mueller. The relationship between confidence in fairness and the appropriateness of pardons for senior officials is nearly identical.

Figure 3

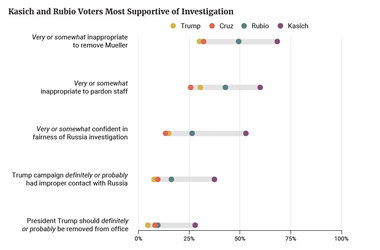

While divisions between political parties are unsurprising, some notable groups of Republicans are more supportive of the Russia investigation and more skeptical of the Trump administration.

Although it took place more than two years ago, the internal divisions made apparent during the 2016 Republican presidential primary are still visible today. By the end of the race, Trump had won 45 percent of the popular vote, while 25 percent went to Senator Ted Cruz, 14 percent to Governor John Kasich, and 11 percent to Senator Marco Rubio.(ii) On the issue of the Russia investigation, there are clear divisions between Trump and Cruz voters — who give nearly identical responses — and Kasich and Rubio voters.

Those who voted for John Kasich and Marco Rubio are far more supportive of the investigation than those who supported Trump. A majority (53 percent) of Kasich voters and about a quarter (26 percent) of Rubio voters are “somewhat” or “very confident” that the Russia investigation is being conducted fairly. Just 15 percent of Trump primary voters and 13 percent of Cruz primary voters say the same.

Similarly, these non-Trump Republican primary voters are more skeptical of presidential interventions in the investigation. A majority of Kasich (68 percent) and nearly half (49 percent) of Rubio primary voters say that removing Mueller would be “somewhat” or “very inappropriate” compared to just three in 10 Trump primary voters (30 percent) and about a third of Cruz voters (32 percent). These differences are similar on the question of pardoning senior officials — with significantly more Kasich (60 percent) and Rubio (43 percent) voters thinking it would be “inappropriate” than Trump (31 percent) and Cruz (26 percent) voters.

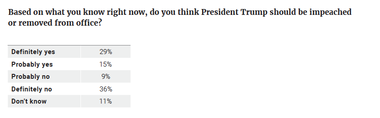

Finally, Kasich and Rubio voters are generally more likely to say the core allegations made against the president are true and believe that he should be removed from office. More than a third (37 percent) of Kasich voters and one in six (16 percent) Rubio voters think that the Trump campaign “definitely” or “probably” had inappropriate contact with Russia. Fewer than one in 10 (8 percent) Trump primary voters say the same. Kasich (28 percent) and Rubio (10 percent) voters are also much more likely to think that Trump should “definitely” or “probably” be removed from office than are those who supported Trump (5 percent) and Cruz (8 percent). This compares to more than four in 10 (45 percent) of all Americans who say the same.

Figure 4

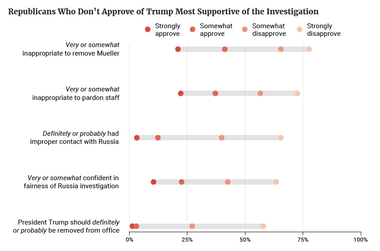

There are also strong differences of opinion between Republicans based on their level of approval and disapproval of the president. Among Republicans and Republican-leaners, a majority either “strongly” (48 percent) or “somewhat approve” (38 percent) of the job Trump is doing as president. About one in eight “somewhat” (7 percent) or “strongly disapprove” (6 percent) of Trump. Those who “disapprove” of the president represent less than 15 percent of those who identify as Republicans.

Those who do not approve of the president are also the most skeptical of his administration and supportive of the Russia investigation. Those Republicans who “strongly” or “somewhat disapprove” of the president are much more likely to say that removing Mueller would be “inappropriate” (78 percent and 67 percent) than those “somewhat” or “strongly” approving of him (42 percent and 21 percent). We see that same ordering when we ask whether it would be inappropriate to pardon senior officials (73 percent and 57 percent vs. 38 percent and 22 percent).

Similarly, a majority of those Republicans who “strongly disapprove” say that the investigation is “fair” (64 percent), that Trump or his campaign had improper contact with Russia (65 percent), and that Trump should be removed from office (58 percent). A smaller but still substantial portion of those who “somewhat disapprove” said the same (44 percent, 40 percent, and 27 percent, respectively). Those Republicans who “strongly approve” (10 percent, 3 percent, and 1 percent) and “somewhat approve” (23 percent, 12 percent, and 3 percent) of the president respond comparably on these three items.

Figure 5

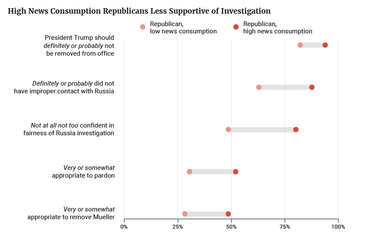

There is also a significant division between Republicans who follow the news “most of the time” and those who follow it “some of the time” or “less.” Attentive Republicans are more supportive of the Trump administration and skeptical of the investigation. Those consuming more news are more likely to say that the president should not be removed from office (94 percent vs. 82 percent), that the Trump campaign did not have improper contact with Russia (88 percent vs. 63 percent), that they are “not confident” in the fairness of the Russia investigation (80 percent vs. 49 percent), and that it would be “appropriate” for the president to pardon senior officials (52 percent vs. 30 percent) and remove Robert Mueller from the investigation (49 percent vs. 28 percent).

This relationship is consistent with a long-standing body of political science research that ties “cues” from partisan elites — messages and information provided by elected officials and those in the media — to opinions among those co-partisans who have a heavy media diet. In this case, Americans are awash in partisan elites attempting to shape opinions about the Russia investigation. Attentive partisans are more likely to receive and adopt these elite opinions than their less attentive co-partisans.

While predictable, this relationship has significant implications for public perceptions of the investigation going forward. Unless the content of those elite signals changes, we should not necessarily expect higher levels of information or news consumption on the part of partisans to act as a moderating force.

Figure 6

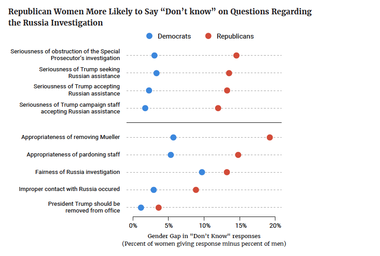

There is also a potential division between men and women within the G.O.P. Republican women are much more likely to answer “don’t know” across many of the questions involving the Russia investigation. Compared to Republican men, Republican women are much more likely to say they “don’t know” about the appropriateness of removing Mueller (16 percent vs. 35 percent), the appropriateness of pardoning senior officials (17 vs. 32 percent), the fairness of the Mueller investigation (7 percent vs. 20 percent), and the possibility of contact between the Trump campaign and Russians (6 percent vs. 15 percent). In addition, Republican women are about twice as likely to give this answer when asked about the seriousness of the four allegations presented in the previous section — with roughly one in five of these women saying “don’t know” to each item.

While women are generally more likely than men to give a “don’t know” answer on surveys,(4) it’s not clear that this explains the differences here. For questions about the Russia investigation, the gender gap in “don’t know” response — the difference between the rates at which women and men give that answer — is systematically higher among Republicans than it is among Democrats. For all but one question, the Republican gender gap is at least twice the size of the Democratic gap (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

(4) This phenomenon — women being more likely than men to answer “don’t know” — is well documented and likely the result of differences in political socialization, learning, and a male propensity to guess even when uncertain. For a fuller discussion, see: Jeffery J. Mondak and Mary R. Anderson, “The Knowledge Gap: A Reexamination of Gender-Based Differences in Political Knowledge,” The Journal of Politics, vol. 66, no. 2, 2004, pp. 492–512, Print.

A recent report from the Voter Study Group, “Testing the Limits: Examining Public Support for Checks on Presidential Power,” found that the American people believe in the rule of law and constitutional checks and balances — at least in the abstract. Last summer, 91 percent of Americans said “the president must always obey the laws and courts, even if he thinks they are wrong” and 81 percent said “members of Congress should provide oversight of the president and executive branch, even if the president is in their same party.”(iii)

The response of political leaders and the public to the outcomes of the Russia investigation over the coming months may tell us a great deal about the degree to which we as a country really believe in these principles. In a deeply partisan moment, do we as a country have the capacity to look at the outcomes of an investigation and make a reasonably impartial judgment about whether wrong doing took place?

The degree to which Democrats and Republicans are already jumping to deeply divergent conclusions should give us all pause. Perhaps more concerning is the significant decline in public faith in our justice system. While no one should be above scrutiny, the willingness of political leaders to attack the integrity and independence of the F.B.I. and Justice Department is worrisome in those cases where evidence of wrong doing is limited.

The data presented in this report provide some solace. The bipartisan belief that the allegations being investigated are serious indicates that we share a common sense of right and wrong across political lines. More to the point, it suggests that strong evidence one way or the other could be persuasive to at least some partisans, especially if bolstered by responsible behavior by at least some political elites.

It also may be comforting that most Americans believe that it is not appropriate for the President to intervene in the investigation. For Trump voters, perceptions about the fairness of the investigation are highly related to whether they think it is appropriate for the President to intervene, reinforcing just how important it will be for investigators, political leaders, and media elites to take steps that increase, rather than decrease, confidence in the system. Bipartisan efforts in the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence to conduct their investigation jointly is one excellent example of a confidence-building effort.

It will be useful to revisit the questions asked in this study as the investigation unfolds and potentially learn what drives both confidence and skepticism in our system of government during times of institutional distress.

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Table 8

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.