Democratic Norms, Elections, Political Parties

Key Findings

On January 6, 2021, a mob of pro-Trump supporters stormed the United States Capitol. The mob came directly from a Trump rally where the president had urged them to “show strength” and told them that “When you catch somebody in a fraud, you are allowed to go by very different rules.”(i)

In the months leading up to the election, Trump had repeatedly claimed that the only way Democrats could win would be through massive fraud. The pandemic shift to mailed ballots gave him and his allies a convenient target for their allegations. After the election, the president doubled down on his claims of fraud. A growing cadre of Republican elected officials and conservative media commentators followed along, pushing the Stop the Steal narrative: Democrats had somehow cheated, and Trump was the rightful winner.

In the months since, Republican politicians across the country have supported the narrative of a stolen election. The embrace has been especially strong in state Republican parties, and especially in states where the contest was relatively close. Republican Party officials who have argued that Biden won the 2020 election fair and square, like Georgia Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and Nevada Republican Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske, have been censured by state party committees.(ii) In Congress, House Republicans voted to remove Representative Liz Cheney from her leadership post for speaking out against the narrative of a stolen election.

The Stop the Steal movement is also driving a new wave of Republican-drafted state laws that restrict voting access — specifically targeting modes of voting favored by Democratic constituencies(iii) — and that change the ways in which elections are administered, empowering partisan state legislatures over professional election administrators and secretaries of state.(iv)

Meanwhile, Trump himself looms as a significant presence and the likely frontrunner in the 2024 Republican primary, should he decide to run. One sign of his sway over the party is the extent to which Republican elected officials at all levels, as well as conservative advocacy groups, devoted themselves to changing the rules of elections, in response to alleged, but unproven, fraud.(v) These developments raise an obvious question: Is this the future of the Republican Party? One way to answer this question is to ask another: What do Republican voters think about Trump and his claims of a stolen election? And more specifically, what other attitudes are most common among Republicans who most strongly believe the election was stolen and are most loyal in their support of Trump?

Republicans widely supported Trump both before and after the election,(vi) and Republicans also widely believe that the 2020 election was stolen.(vii) But we know less about which Republicans are most bought into the claim of a stolen election and which Republicans are most devoted to Trump.

A typical approach when answering questions such as these is to focus on specific and frequently binary polling questions, such as whether Republicans think of themselves as Trump Republicans or Party Republicans;(1) or whether Republicans believe Joe Biden fairly won the election or that Biden’s win was due to widespread fraud.(2) It’s important to keep in mind that any singular polling question misses the gradations of support or ambivalence.

In this analysis, I take a different approach. Using data from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey), I combine answers across numerous survey questions to generate various “scores” that reflect more complexity and diversity of attitudes among Republican voters. By averaging across multiple questions, we can see how deeply devoted some Republicans are to both the stolen election narrative and to Trump, as well as what other attitudes and outlooks are most prevalent among these devotees.

The results of this analysis confirm much of what many others have observed — Republican support for Trump and the stolen election narrative is broad but not universal. This variation among Republicans is important because it allows us to identify the characteristics of the most devout supporters and better understand the challenges the Republican Party faces in moving past the grievance politics of Trump and his acolytes.

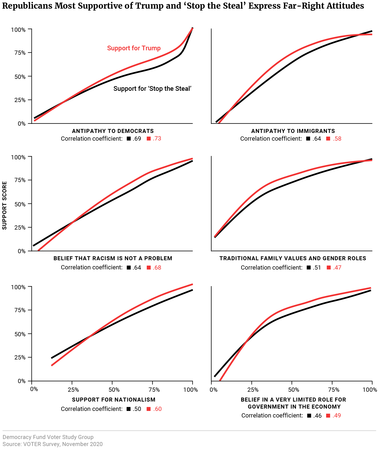

This analysis shows Republicans most committed to both Trump and the narrative of election fraud also tend to have the highest levels of antipathy toward Democrats and toward immigrants, strongest belief that racism is not a problem, highest levels of nationalism, greatest support for traditional family values and gender roles, and strongest belief in a very limited role for government in the economy.

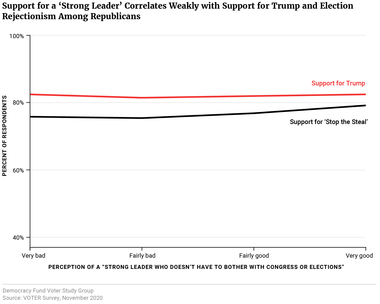

However, this analysis also suggests that one other common perception — specifically that Trump’s strongest supporters and the biggest devotees of Stop the Steal are uniquely opposed to democracy and instead crave a “strong leader” — does not hold up to scrutiny.

(1) See https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/meet-the-press/what-if-america-s-four-politicalparties-n1255450, suggesting that Republicans are split between Trump Republicans and Party Republicans.

(2) While 60% of Americans overall believe President Joe Biden fairly won the presidential election, 60% of Republicans instead believe Trump’s claims that Biden’s win was due to widespread voter fraud despite a lack of credible evidence.” https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2021/04/05/morethan-half-of-republicans-believe-voter-fraud-claims-and-most-still-support-trump-poll-finds/.

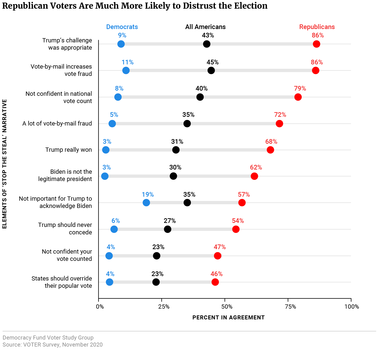

The November 2020 VOTER Survey asked numerous questions about the election’s legitimacy, which garnered varying levels of support among Republicans.

The Stop the Steal narrative consists of three main aspects:

Rather than rely on any single question, I use an algorithm to combine responses to 10 questions that touch on these three aspects into a single “score” that measures the extent to which an individual respondent rejects the election.(3) These questions, grouped by the aspect they explore, are as follows:

Amount of Fraud in the Election

The Real Winner

The Appropriate Response

Figure 1 shows the percentages of Democrats, Republicans, and all voters who give responses consistent with support for Stop the Steal. While Democrats give little purchase to Trump’s allegations, Republicans vary in the depth of their belief in all aspects of a stolen election.(4) Among Republicans, the most widely supported propositions are that it was appropriate for Trump “to file lawsuits challenging the election results in several states” (86 percent) and that vote-by-mail increases vote fraud (86 percent). Only two propositions registered less than 50 percent among Republicans — not being confident that their own vote counted (47 percent) and believing that it was appropriate for “Republican legislators in states won by Joe Biden to try to assign their state’s electoral votes to Donald Trump” (46 percent).

This final proposition reflects one of the most extreme positions in the Stop the Steal narrative — support for state legislatures overriding the popular vote in their states in favor of the losing candidate. As Republican state legislatures push voting laws, they continue to consider provisions that would give partisan state legislatures more power in certifying election results. Had state legislatures been vested with more of these powers in 2020, they may well have used them to override decisions by nonpartisan election administrators and secretaries of states. As fights over election law continue to play out, many observers are wondering exactly how far elected Republicans will go.

While all propositions are generally supported by Republicans, the electorate as a whole looks very different. No single proposition garners anywhere near to majority agreement among the overall electorate. The most widely supported idea among all voters is that vote by-mail increases fraud (45 percent).

(3) Specifically, I use the “lavaan” package in R to extract a “factor score” by placing all the questions along a single latent dimension.

(4) For ease of interpretation, I’ve combined the somewhat/strongly agree and disagree categories in Figure 1.

Figure 1

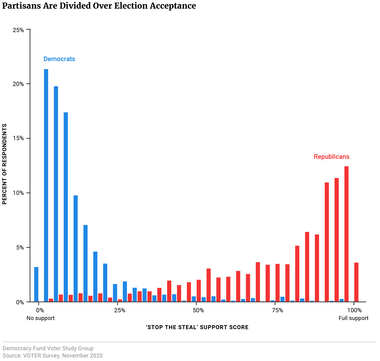

Since these propositions receive varying degrees of support and reflect varying concerns, no single one can conceivably stand as the “right” measure of support for Stop the Steal. To take advantage of the full range of information provided by these survey questions I’ve combined them into a single score, as described above. This measure is scaled from 0 to 100, with a score of 100 representing full acceptance of every element of Trump’s electoral claims and a score of 0 representing the complete opposite — total rejection of these claims.

Democrats almost universally reject claims of a fraudulent election, though some Democrats express modest openness to a few elements of the Stop the Steal narrative. By contrast, Republicans’ Stop the Steal support scores tend to be much higher, but as Figure 2 shows, there is notable variation among Republicans in the extent to which they believe in all the elements.

Figure 2

A standard political science explanation for the development and evolution of Americans’ political views is that people are mostly following elite leadership. In short, when political elites signal their support for, or opposition to, particular ideas, those who affiliate with them politically follow suit. And the more widely those ideas are repeated in the media and echoed by other politically aligned elites, the more likely fellow partisans in the electorate are to believe them.(viii) From this perspective, widespread support for the Stop the Steal narrative follows naturally from widespread devotion to Trump. Trump, the de facto leader of the Republican Party, repeatedly claimed that there was massive fraud and the election was stolen. In response, many Republican voters adopted those views.

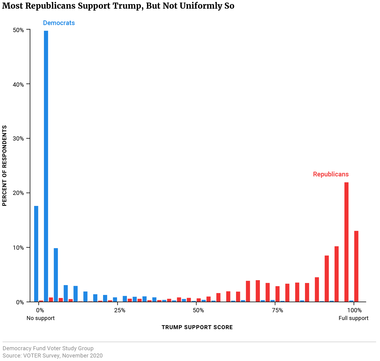

Again, rather than relying on a single question, I combine responses to multiple questions (which allow respondents to qualify their support as either very or somewhat favorable or supportive) into a broader “Trump support score.”(5) To gauge support for Trump among Republicans, the November 2020 VOTER Survey asked respondents to rate their general approval and favorability of Trump, and also to rate him on specific issues such as his handling of COVID-19, the economy, and race relations. Most Republicans are very strongly supportive of Trump. But some are less supportive. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the “Trump support score” among Republican respondents,(6) revealing more gradations than the traditional binary approve/disapprove ratings can provide.

(5) For question details, see the Appendix.

(6) Throughout this report, Republicans include “leaners” (voters who initially identify as independent, but when pressed, admit that they almost always support Republican candidates).

Figure 3

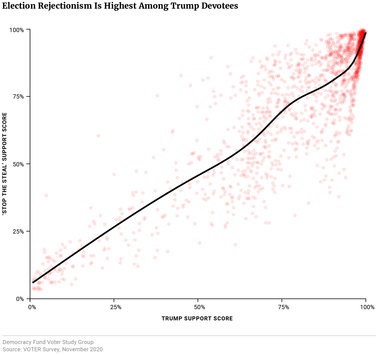

Consistent with the elite-driven model of public opinion, the most devoted Trump supporters are also most supportive of the stolen election claims, and the statistical correlation between the two scores is extremely high.(7) The more completely a Republican voter supports Trump, the more completely that voter rejects the election results and wholly supports the Stop the Steal narrative. And among the most devoted Trump supporters, there is a sharp uptick in their embrace of the stolen election narrative.

(7) The correlation is 0.82.

Figure 4

But this is not the whole story. After all, the Republican narrative of Democrats “stealing elections” through widespread “fraud” did not originate with Trump. Republican elites have been raising alarms about “voter fraud” for more than two decades, using these assertions to justify increasingly stringent voting requirements that target Democratic constituencies, particularly voters of color. Republican trust in elections has declined steadily during this period.(ix) However, as two recent Democracy Fund Voter Study Group reports show, 2020 was also very different; with the president and party leaders repeatedly sowing distrust, faith in the fairness of the election and the legitimacy of the winner plummeted compared to previous elections.(x)

Nonetheless, these attitudes of distrust are not universal among Republicans. Nor is devotion to Trump universal. Indeed, some Republicans who are devoted to Trump are less bought into the Stop the Steal narrative than others who are equally devoted, while some Republicans who are less devoted to Trump register more distrust for the election. Why is that?

While we cannot fully inhabit the minds of Republican voters to know what explains their support for both Trump and for rejecting the election, we can examine the kinds of attitudes and beliefs that correlate most strongly with support for Trump and election rejectionism. We now turn to six additional factors: antipathy toward Democrats, antipathy toward immigrants, belief that racism is not a problem, support for nationalism, support for traditional family values and gender roles, and belief in a very limited role for government in the economy.

These attitudes all loom large in the rhetoric of Republican candidates and messaging, so it’s helpful to look at how they relate to Stop the Steal for clues about the future of the party.

The top takeaway is that the Republicans most deeply supportive of Trump and the Stop the Steal narrative hold far-right attitudes across all of these dimensions. Figure 5 presents the correlates of six underlying factors, providing a visual overview.

Figure 5

The discussion that follows covers each of these issues in more detail, but a few big-picture takeaways emerge from this data.

First, the strongest correlation of both support for Trump and Stop the Steal is antipathy toward Democrats. Above all else, what the strongest supporters of both the former president and his election narrative have most in common is disliking Democrats.

Second, both support for Stop the Steal and Support for Trump strongly correlate with antipathy toward immigrants and belief that racism is not a problem. These correlates are larger than the more traditional hallmarks of conservatism, like traditional family values and gender roles, and belief in a limited role for government in the economy. To be sure, Republicans most enthusiastic about Trump and least trusting of the election results also tend to hold traditionally conservative views on family and gender and on economic issues — just not as reliably as they dislike immigrants, reject the problem of racism, and especially dislike Democrats. Nationalism — here measured largely as believing in the unique greatness of America — shows up as a stronger correlate of Trump support than it does of support for Stop the Steal.

A growing number of partisans are motivated by what political scientists call “negative partisanship,” where intense dislike of the other party is the strongest factor driving behavior, and the primary goal is keeping the other party out of power. As political scientists Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster explain, “In today’s environment, rather than seeking to inspire voters around a cohesive and forward-looking vision, politicians need only incite fear and anger toward the opposing party to win and maintain power."(xi) A less academic version of this is the joy that many Republicans seem to feel in "owning the libs."

The implication is that if negative partisanship is operative, Republicans would be motivated to reject the election results primarily because they can’t stand the thought of Democrats winning. To be sure, the intense dislike of an opposing party springs from the values and groups for which the opposing party stands. But partisanship itself has become a standalone identity in today’s politics.(xii) So perhaps what Republicans oppose most of all is simply “Democrats.” Under this logic, Republicans with the strongest dislike of Democrats would be most likely to reject the election.

“Democrat dislike” is a score composed of several survey questions. In the September and November 2020 VOTER Surveys, respondents were asked about their feelings toward several prominent Democratic politicians (Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Bernie Sanders). They were also asked to place Democrats on a feeling thermometer, rating their warmth toward Democrats from 0 (coolest) to 100 (warmest). The Democrat dislike score combines all these ratings into a single score. Thus, a respondent who strongly disapproves of every Democrat across multiple surveys and rates Democrats at 0 on a feeling thermometer would have the highest possible dislike score, 100.

Strong dislike of Democrats is an important and robust characteristic of Trump supporters and Stop the Steal adherents. “Negative partisanship” stands out as particularly important, especially at the high ends of the scale.

Immigration is the issue that launched Trump’s candidacy. Building “The Wall” on the Southern border quickly became Trump’s signature campaign issue, and a rallying cry for Trump supporters.

Throughout his political career, Trump has falsely alleged widespread voting by undocumented immigrants and claimed that Democrats plan to expand immigration in order to generate more Democratic voters. More specifically, in October 2016, Trump claimed that undocumented immigrants were being allowed to cross the border for this express purpose, saying, “they’re letting people pour into the country so they can go and vote.”(xiii)

Similarly, in September 2016, Trump claimed that if he didn’t win the 2016 election, “I think this will be the last election that the Republicans have a chance of winning because you’re going to have people flowing across the border, you’re going to have illegal immigrants coming in and they’re going to be legalized and they’re going to be able to vote and once that all happens you can forget it.”(xiv) Despite winning that election, Trump then falsely claimed noncitizen voting accounted for Hillary Clinton’s popular vote victory margin. On November 26, 2016 he tweeted, “In addition to winning the Electoral College in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.”(xv) Republicans emphasized immigration as a key campaign issue in the 2018 mid-terms, focusing extensively on the threat of a “migrant caravan.”(xvi) In 2020, half of Trump’s election ads discussed immigration.(xvii) Trump then made similar false allegations that noncitizen voting had cost him a victory in 2020.(xviii) Conservative commentators are now embracing “replacement theory” — the idea that an influx of immigrants will “replace” native-born Americans, and vote Democrats into permanent power. As Senator Ron Johnson (R-WI) recently posed in the form of a question, do Democrats “really … want to remake the demographics of America to ensure their — that they stay in power forever? Is that what’s happening here?”(xix)

Several recent studies have documented that some white Americans view the coming of an increasingly diverse nation, and especially one in which white people are no longer a numerical majority, as a real threat, demanding a defensive response.(xx) Trump’s activation of anti-immigration attitudes and fear of declining social status among certain white populations contributed to his support among both Republican primary voters and general election voters.(xxi)

To measure attitudes on immigration I combine eight questions from the November 2020 VOTER Survey into a single score. These questions ask about how much immigrants detract or add to American society, as well as whether immigration should be decreased or increased.(8) Not surprisingly, immigration attitudes correlate with support for both Trump and Stop the Steal. However, the statistical relationship is slightly different for each. The connection between immigration and Trump support flattens out among the most anti-immigrant Republicans, suggesting that the most devoted Trump supporters are no more anti-immigration than those who are merely enthusiastic Trump supporters. The most devoted believers in Stop the Steal are the most anti-immigration Republicans. The correlation between anti-immigration attitudes and Stop the Steal is even higher than the correlation between Stop the Steal and Trump support.

(8) For all questions, see the Appendix.

In his official GOP response to Biden’s first joint address to Congress, Republican Senator Tim Scott said that “America is not a racist country.”(xxii) This echoed a sentiment many Republican politicians have expressed, including Donald Trump, who claimed he didn’t have a “racist bone in his body.”(xxiii)

Yet, despite Scott’s protestations, the events of 2020 put contested race relations and racial justice at the center of American political life. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, millions of Americans protested against what they saw as racially motivated police brutality. However, many Republicans saw both these protests and the larger Black Lives Matter movement as a genuine threat. President Trump called the protestors “thugs”(xxiv) and conservative media emphasized the most violent and destructive elements of the movement as widely representative.(xxv) Trump also tweeted, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” seeming to encourage violence in echoes of rough policing of 1967 civil rights protests.(xxvi) Kyle Rittenhouse, the 17-year-old Trump supporter from Antioch, Illinois, who is accused of murdering two people during protests against police brutality in Kenosha, Wisconsin, became a folk hero(xxvii) to many on the political right.(xxviii) In the 2020 campaign, Trump elevated heavily racialized law-and-order themes, attempting to convince voters that, “They want to destroy our suburbs.”(xxix) Republicans turned to demonizing the BLM movement in campaign ads, playing on threats of what a Democratic victory would mean.(xxx) The Republican National Convention was less than subtle in placing racial issues at the center of the campaign.(9)

Thus, to the extent that Republican voters’ feeling toward Black Americans makes them receptive to threats of disorder and chaos, they might also be more receptive to the claim of a stolen election as a way to preserve Republican leadership to prevent such disorder. Moreover, for decades, Republican charges of voter fraud have been closely tied to “urban” voting, with unsubstantiated claims that largely Black cities like Detroit and Philadelphia have long been hotbeds of cheating.(xxxi) While we can’t test this directly, one proxy is the extent to which respondents deny that any discrimination or racism exists in America, and the extent to which existing inequities between Black and white Americans is due to structural racism or work ethic.(xxxii) To measure this, I calculate a score from 15 questions asked in the September 2020 VOTER Survey that measure attitudes toward Black people, ask about the levels of racial privilege and fairness in society, and ask about recent killings of African American men by police.

Republicans most likely to believe that racism and discrimination are not a problem are also the most devout believers in the Stop the Steal narrative. These attitudes also correlate with support for Trump; the Republicans most ardent in their belief that racism is not a problem on average have the highest levels of support for Trump.(10) This is consistent with numerous previous studies that have found similar relationships between racial attitudes and enthusiasm for Trump.

(9) “The Republican Party has clearly leaned into a kind of white grievance politics,” said Hakeem Jefferson, a professor of political science at Stanford University. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/25/us/politics/the-rncs-not-so-subtle-undertones.html.

(10) The correlation between anti-Black attitudes and support for Trump is 0.68; the correlation between anti-black attitudes and support for Stop the Steal is 0.64.

Another aspect of the contemporary Republican Party is “traditional family values.” In fights over gay marriage, abortion, transgender rights, traditional women’s roles, and the extent to which the “Me Too” movement went too far, longstanding culture-war issues have continued to play out as polarizing wedges, with many ultra-religious Christian groups remaining closely aligned with Republicans and Trump in particular.

As with the other issues discussed in this report, I combine several questions that address these views (all of which are closely correlated with each other) into a traditional family values and gender roles index.

As with other issues, Republicans who hold the most far-right views on family values and gender roles are also, on balance, the most supportive of both Trump and Stop the Steal, consistent with the narrative that these Republicans are most concerned about Democratic control and what it means. However, the correlations here are not as strong as those with antipathy toward immigrants and the belief that racism is not a problem.

“You know what I am?” Trump asked at a November 2018 campaign rally for Ted Cruz. “I’m a nationalist. OK? I’m a nationalist.” The crowd applauded. “Use that word,” Trump went on. “Use that word.”(xxxiii)

Trump’s “America First” slogan certainly has strong elements of nationalism. And throughout his campaigns and presidency, he frequently called Democrats “globalists” — the obvious enemy of nationalists. In his Cruz rally speech, Trump went on: “Radical Democrats want to turn back the clock. Restore the rule of corrupt, power-hungry globalists. You know what a globalist is, right?” He continued: “A globalist is a person that wants the globe to do well, frankly not caring about our country so much. And, you know what? We can’t have that.”(xxxiv) In “America First” and the “nationalist” label, some conservatives have seen a positive vision of America as a nation with strong traditions and a binding collective identity that are essential foundations to our prosperity. Without a common and unifying national identity and culture, such conservatives warn, we are left with nothing holding us together, and inevitable fracture. Critics, mostly on the left, have argued that such nationalism is actually white ethnonationalism and is, thus, the opposite of unifying. This debate has played out in various ways over the last several years, but perhaps most prominently in controversy over “The 1619 Project,” a New York Times Magazine feature named for the year in which enslaved Africans are thought to have been first brought to the United States. This piece opened a debate on the centrality of slavery to the founding story of America, and more broadly, to what extent Americans should be proud of our history and traditions, as well as critical of our history.(xxxv)

Nationalism is obviously a complicated concept, and certainly many differ on how best to measure and characterize it. For purposes of this analysis, I combine a battery of questions asking respondents about how much pride they have in the United States, its history, and the extent to which the United States is a global model.(11) Notably, nationalism correlates more closely with support for Trump than with support for Stop the Steal.

(11) See the Appendix for details.

During the 2020 election season, President Trump attempted to frame the election as a referendum on “whether we save the American Dream or whether we allow a socialist agenda to demolish our cherished destiny.”(xxxvi) This line of argument reflects the more traditional Republican approach to making elections about the threat of “big government.”

Though Trump may have run away from traditional conservative economics in the 2016 campaign, his signature 2017 tax cuts and aggressive deregulations moved his governing agenda into a more familiar Republican economic direction. Though it’s unclear how effective his attempts to portray the Biden agenda as socialist were across the country, some have suggested that this effort was effective with Latin American voters, particularly in Florida.(xxxvii)

To measure preference for a limited government role in the economy, I combine seven survey questions into a single index, asking about taxation, poverty, healthcare, and the social safety net.(12) As with the other issues discussed in this report, the most extreme-right values on the scale for this factor correlate with the highest levels of support for both Trump and for Stop the Steal.

(12) See the Appendix for details.

Another possibility is that both support for Trump and rejection of the election results reflects support for “authoritarianism” among voters. Previous Voter Study Group reports have examined support for a “strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections” and other alternatives to democracy, finding that roughly a quarter of Americans express some support for such a system, and that those supporting authoritarianism express stronger support for Republicans than Democrats.(xxxviii) Many commentators have described both Trump and his supporters as authoritarian and fascist for their disregard of civil liberties and basic democratic norms and their embrace of ethnonationalism.(xxxix) However, both “authoritarian” and “fascist” are contested categories, with considerable disagreement among scholars as how to define them and how to measure them.

Here, I use the survey question that asks about a “strong leader.” Among Republicans, support for both Trump and for the Stop the Steal narrative are slightly higher among those who believe that a more authoritarian form of rule is better. But compared to the other factors discussed in this analysis, overt enthusiasm for more authoritarian rule is not a distinct value among Republicans who most strongly reject the election or show the most devotion to Trump. Instead, consistent with other recent analyses, both hyperpartisanship and ethnic antagonism are far greater threats to democracy than direct support for alternatives to democracy.(xl) After all, many of the most fervent supporters of Stop the Steal believe they are the ones who are preserving free and fair elections and following the Constitution. These voters tend to be disproportionately active and civically engaged.(13) By contrast, support for a strong leader is most prevalent among voters who are largely disengaged in politics.(xli)

(13) “For example, at least 50 percent of these MAGA supporters have been politically active — signing petitions, contacting their representatives, participating in boycotts or donating to campaigns. Beyond that, roughly 45 percent report they’ve attended political meetings, 35 percent attended rallies, and 30 percent volunteered for campaigns.” Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/03/02/why-gop-cant-quit-trump/.

Figure 6

As Republican Party officials across the country attempt to navigate the future of the party, both former President Trump and the narrative of a stolen election continue to drive the national discussion. As Republican states continue to restrict the franchise around manufactured concerns of “electoral integrity,” and Republican leaders both local and national work to purge the party of those who accept the legitimacy of the 2020 election results, there are lingering questions about whether relitigating the 2020 election is a viable path forward for the GOP.

To be sure, those whose preferred candidate has won the electoral vote typically report more confidence in election results than those whose candidate has lost.(xlii) Thus, we should hardly be surprised that Democrats had more confidence in the 2020 electoral results than Republicans did. Winners always have more confidence in the results.

But the 2020 election stands out compared to previous elections. As described in the Voter Study Group report Crisis of Confidence, compared to electoral losers in previous years, Trump supporters were less confident that their vote was counted accurately, less likely to accept Biden as the legitimate president, and more likely to say that permanent harm had been done to the United States as a result of the election process than the supporters of losing candidates in previous elections. The unprecedented campaign by a sitting president to discredit the results of an election he lost resulted in unusually high and, at this point, long-lasting doubts about the credibility of the election and the incoming administration.

While opinion among Republican voters varies, the preponderance of GOP voters shows deep levels of support for both Trump and for the Stop the Steal narrative. The strongest support for both Trump and for rejecting the election comes from Republican voters who hold a constellation of traditionally far-right attitudes on race, immigration, nationalism, family values and gender roles, and economics, and who have a deep dislike of Democrats. Or put a different way, Republicans who are most skeptical of both Trump and the Stop the Steal narrative tend to have more middle of-the-road attitudes across the board, but especially on immigration, and they do not harbor deep dislike of Democrats.

The analysis here has combined multiple questions to generate “scores” for each of these attitudes, rather than relying on singular questions. These scores are helpful because they generate a broader continuum of opinion and allow us to analyze Republican opinion with more nuance. There are no clear and simple dividing lines among Republicans, but rather gradations of support for Trump and for rejecting the election. To the extent that divides emerge, they will rely on partisan leaders to shape them and force them open.

It’s clear that some Republicans accept the legitimacy of the 2020 election, are eager to move past Trump, have more moderate positions on race and immigration, and have at least a degree of acceptance of Democrats. But they are clearly a minority within the party — and, at this point, there is not a clear path for such a faction to retake control of the Republican Party.

A broader view shows that the Republican Party’s devotion to Trump and their rejection of the legitimacy of the 2020 election are decidedly minority positions among the entire electorate, even if they are dominant positions in the Republican Party. And in America’s two-party system, a national minority can win elections and maintain power, so long as it is dominant in one of the two major parties. Thus, to the extent that the Republican Party is focused on righting the alleged wrongs of the 2020 election by changing the rules and wresting power from independent election administrators, American democracy is likely to become even more contested and unstable.

Presented below are abbreviated versions of the many questions included in the scores used throughout this report. For full question wording and response options to these questions, please consult the crosstabs available here.

Trump Support

Democrat dislike

Antipathy toward immigrants

Belief that racism is not a problem

Nationalism

Traditional family values and gender roles

Limited role of the government in the economy

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.