Executive Branch, Ideology, Immigration, Religion

Key Findings

Increasing political polarization and rising conflict over identity, race relations, immigration, and L.G.B.T. rights have left two increasingly divided extremes with a seemingly elusive moderate middle.(1) Many have come to view religious institutions, largely due to their opposition to same-sex marriage, as a major contributor to this ever-increasing divide — a catalyst for increased intergroup societal conflict, rather than a possible cure. However, research from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group’s VOTER Surveys (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) find that religious participation may serve a moderating function in our politics, particularly among conservatives.(2) These national surveys find that Donald Trump voters who attend church regularly are more likely than nonreligious Trump voters to have warmer feelings toward racial and religious minorities, be more supportive of immigration and trade, and be more concerned about poverty. These data are important because they demonstrate how private institutions in civil society can have a positive impact on social conflict and reduce polarization.

(1) The share of Americans who worry about race relations has doubled since 2014 (17 percent to 37 percent), and the number very dissatisfied with the state of race relations has tripled (11 percent to 36 percent); “Race Relations,” In Depth Topics A to Z, Gallup News, Gallup. Available at: https://news. gallup.com/poll/1687/race-relations.aspx; See also Betsy Cooper, Daniel Cox, Rachel Lienesch, and Robert P. Jones, “Anxiety, Nostalgia, and Mistrust: Findings from the 2015 American Values Survey,” Report, Public Religion Research Institute, November 2015. Available at: https://www.prri.org/research/ survey-anxiety-nostalgia-and-mistrust-findings-from-the-2015-american-values-survey/.

(2) Data in this brief come from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group's 2018, 2017, and 2016 VOTER Surveys.

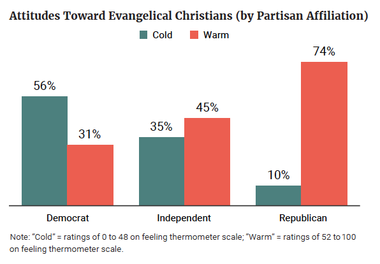

Figure 1

Left-right culture wars over L.G.B.T. rights — particularly government sanction of same-sex marriages — have likely soured many Democrats’ views of Christians. Indeed, a majority (56 percent) of Democrats report unfavorable feelings toward evangelical Christians.(3) This, in large part, may be a response to the 64 percent of churchgoing Christians who oppose legalized same-sex marriage and half have cool feelings toward L.G.B.T. people, and that the more frequently people attend church, the more negative their attitudes are likely to be toward gay men, lesbians, and also feminists. Thus, antagonism toward religious institutions is often grounded in the idea that religion is a source of exclusion and oppression rather than inclusivity and tolerance. Such views are succinctly articulated by a bumper sticker from the Richard Dawkins Foundation, “There is no war on religion: Only opposition of intolerance, oppression, hatred, and stupidity.”

It may surprise some readers, however, to learn that religious participation may moderate conservatives’ attitudes on other important culture war issues, particularly matters of race, immigration, and identity. Given that the rise of Donald Trump has increased the salience of these issues, this brief uses the 2016, 2017, and 2018 VOTER Surveys to examine how religious and nonreligious people who voted for Donald Trump think about these important issues.(4)

(3) In contrast, far fewer Republicans (10 percent) and independents (38 percent) have unfavorable views of evangelical Christians.

(4) This study examines Trump voters of all racial backgrounds. The racial composition of Trump voters does not vary considerably by church attendance. For instance, 84 percent of Trump voters who attend church more than once a week are white as are 81 percent of those who never attend religious services. Therefore, more favorable attitudes toward racial minorities among very devout Trump voters are not due to a significantly more diverse pool of religious Trump voters.

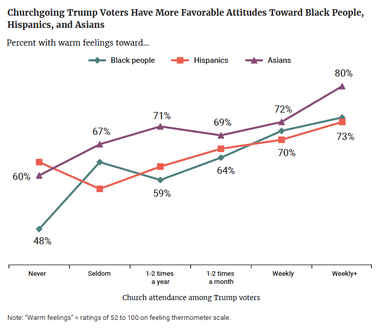

Conservatives’ views of black people, Hispanics, and Asians improve the more frequently conservatives attend religious services. Specifically, favorable feelings toward black people increase from 48 percent among Trump voters who never attend church to 73 percent among those who attend more than once a week — a 25-point increase. Similarly, favorable feelings toward Hispanics and Asians increase from 63 percent and 60 percent, respectively, among secular Trump voters to 72 percent and 80 percent, respectively, among churchgoing Trump voters.

Figure 2

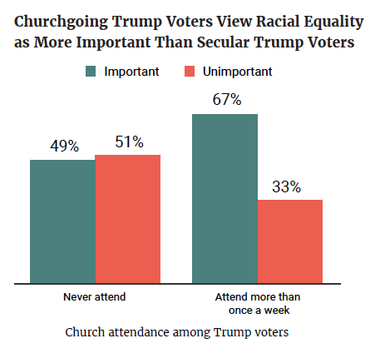

Frequent conservative churchgoers also say they care more about racial equality. More than two-thirds (67 percent) of churchgoing conservatives say racial equality is an important issue to them personally. In contrast, 51 percent of nonreligious conservatives say racial equality is not an important issue.

Figure 3

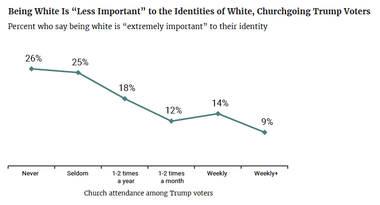

A conservative’s own racial identity also becomes less salient to them the more frequently they attend church. Indeed, nonreligious white Trump voters are about three times as likely as churchgoing white Trump voters to say their white racial identity is “extremely important” to them (26 percent vs. 9 percent).

Reduced emphasis on their own racial identity might contribute to conservative churchgoers being less concerned about future prospects of a so-called “majority-minority” nation. While six in 10 churchgoing Trump voters agree that demographic change will enrich American society, less than half (47 percent) of secular Trump voters agree.

Figure 4

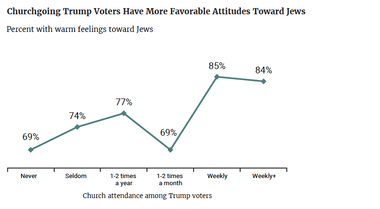

Trump voters’ attitudes toward religious minorities, including Jews and Muslim Americans, also warm according to church attendance.

For instance, very devout Trump voters are 17 percentage points more likely than nonreligious Trump voters to have favorable feelings toward Jews (85 percent vs. 68 percent).

Figure 5

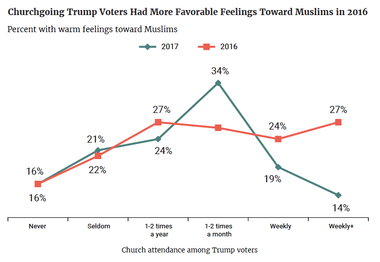

Although Trump voters’ views of Muslims follow a similar pattern, attitudes across the board are less favorable and have shifted downward since 2016.

In the 2016 VOTER Survey, churchgoing Trump voters were nearly twice as likely as secular Trump voters to have favorable feelings toward Muslims (27 percent vs. 16 percent). Trump voters who attend church frequently were also less enthusiastic about implementing a temporary ban on Muslims immigrating to the United States. At the time, very frequent churchgoers were 20 percentage points less likely than secular Trump voters to “strongly” favor a temporary travel ban on Muslims entering the U.S. (34 percent vs. 54 percent).(5)

Figure 6

(5) Majorities of Trump voters regardless of religious attendance support the travel ban either “strongly” or “somewhat,” including 67 percent among Trump voters who attend church more than weekly and 83 percent among those who never attend.

However, after President Trump issued several executive orders restricting travel to the U.S., opinions changed. The 2017 VOTER Survey found that churchgoing Trump voters were about as likely as secular Trump voters to have warm feelings (14 percent vs. 16 percent) toward Muslims. Strong support for the travel ban also increased across the board, but frequent churchgoers remained less enthusiastic than secular Trump voters (58 percent vs. 67 percent reported that they “strongly favor” the travel ban). Even still, the gap narrowed to nine percentage points between nonreligious and religious Trump voters. These data indicate that, at least on some issues, partisanship and a desire to follow the party’s leader may diminish the possible moderating effects of religious participation.

Despite increased support for the travel ban, majorities of Trump voters, regardless of religious observance, oppose denying Muslims who are U.S. citizens the right to vote.(6) Even still, churchgoers are far more “strongly opposed” to such a restriction than nonreligious Trump voters (63 percent vs. 48 percent), the 2017 VOTER Survey found.

(6) Among all Trump voters, 80 percent oppose denying Muslims who are U.S. citizens the right to vote, compared to 92 percent of Hillary Clinton voters.

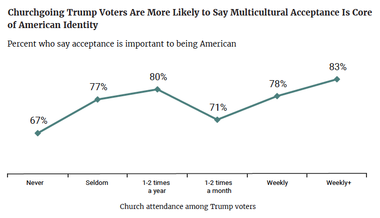

Consistent with these findings, churchgoing Trump voters are more likely to agree that acceptance of racial and religious diversity is at the core of American identity. Eighty-three percent of Trump voters who attend a religious service more than once a week say it is “very” or “fairly important” to accept people of diverse racial and religious backgrounds to be “truly American,” compared to only two-thirds (67 percent) of nonreligious Trump voters — a 16-percentage-point difference.

Figure 7

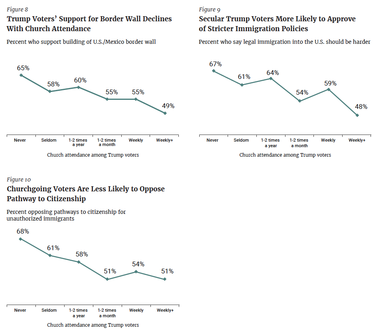

Religious participation also correlates with attitudes toward immigrants and the immigration system. Churchgoing Trump voters are less concerned about in a number of dimensions.

Figures 8-10

Trump voters who never or rarely attend religious services are considerably more concerned about immigration and take a more negative view of it than religiously observant Trump voters. While more than two-thirds (67 percent) of secular Trump voters say immigration is a “very important” issue, less than half (48 percent) of very regular churchgoers agree. Furthermore, nonreligious Trump voters are nearly 20 percentage points more likely than churchgoing Trump voters to oppose a pathway to citizenship for the undocumented, to want a border wall, to support making the legal immigration process more arduous, and to believe illegal immigration drains the economy:

Figure 11

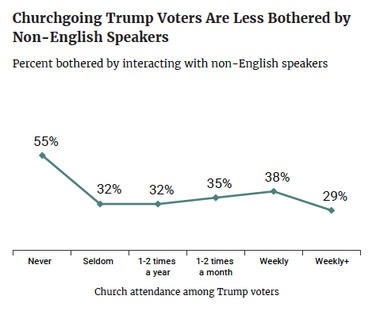

This isn’t just about policy. Secular Trump voters are also more bothered by interactions with non-English speakers than are churchgoing Trump voters. In fact, a majority (55 percent) of Trump voters who never attend church “strongly agree” that it bothers them to interact with immigrants who speak little or no English. In contrast, about a third of Trump voters who attend religious services at least once in a while report this as a salient frustration.

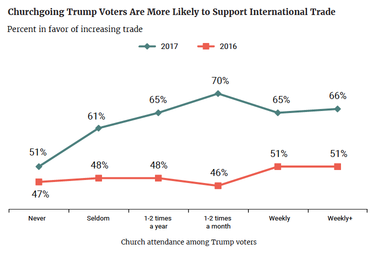

Although trade is a separate issue from immigration, attitudes about trade often correspond to feelings about an increasingly interconnected world — which includes immigration. Indeed, we find a familiar pattern in which nonreligious Trump voters are less optimistic about trade, compared to religious Trump voters. While 51 percent of secular Trump voters favor increasing trade with other countries, two-thirds (66 percent) of churchgoing Trump voters favor doing so.

Figure 12

Interestingly however, immediately after the 2016 presidential election, religious and nonreligious Trump voters had similar attitudes about increasing trade (just 51 percent and 47 percent of each group supported it, respectively). Perhaps because Trump made trade a salient issue during his campaign, his supporters fell into line behind him. Partisanship combined with Trump’s negative rhetoric about trade may have equalized conservatives’ attitudes on the issue regardless of religious participation. As with our finding concerning attitudes on the travel ban, partisan loyalties may reduce the possible moderating effects of religion on attitudes.

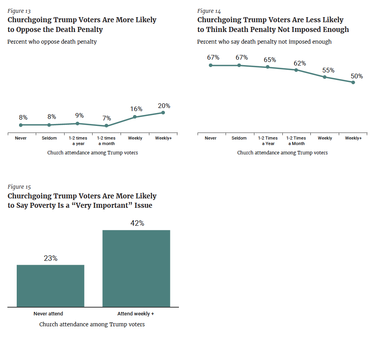

Most conservatives favor the death penalty; however, opposition to capital punishment rises with church attendance. Very frequent churchgoing Trump voters are about two and a half times as likely as secular Trump voters to oppose the death penalty (20 percent vs. 8 percent). Similarly, Trump voters who are very frequent churchgoers are about 20 percentage points less likely than nonreligious Trump voters to think the death penalty ought to be imposed more often (50 percent vs. 67 percent).

Figures 13-15

Religious Trump voters are more concerned about poverty than are nonreligious Trump voters. Trump voters who attend church at least once a week are nearly twice as likely as secular Trump voters to say that poverty is a “very important” issue to them (42 percent vs. 23 percent).

This does not mean, however, that churchgoing conservatives favor a larger welfare state more than secular conservatives. Religiously observant and nonobservant Trump voters alike want the Republican Party to prioritize reducing the size of government (83 percent and 85 percent, respectively) and agree it is not the federal government’s responsibility to ensure everyone has health care coverage (78 percent and 73 percent, respectively). In fact, Trump-voting churchgoers are more likely to favor repeal of the Affordable Care Act (89 percent vs. 76 percent) and to oppose government “doing more” to reduce income differences between rich and poor (71 percent vs. 58 percent) than their secular counterparts. They hold these views despite both groups having fairly similar incomes (Table 1).

Some might interpret these results to mean that religious conservatives only say they care about poverty because they believe it is socially desirable to do so but don’t want to take action with intent to alleviate poverty. However, other data in the survey suggest that religious conservatives may turn to private remedies rather than more government action to help people in need.

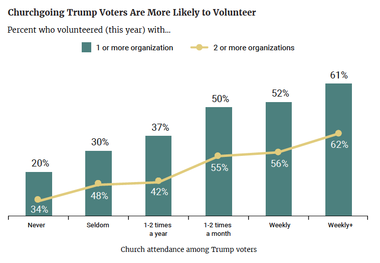

Indeed, religious Trump voters are more likely than nonreligious Trump voters to do volunteer work. For instance, while 61 percent of very frequent churchgoers among Trump voters volunteered at least once in the past 12 months, only 20 percent of secular Trump voters did.(7) And it wasn’t simply volunteer work with their own church. Among only those Trump voters who volunteered in the past year, frequent churchgoers (62 percent) were about 30 percentage points more likely to have volunteered with two or more organizations (and thus not just with their own church) than were secular Trump voters (34 percent).

(7) Data on volunteering comes from the panel baseline survey of the 2012 Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project (CCAP).

Figure 16

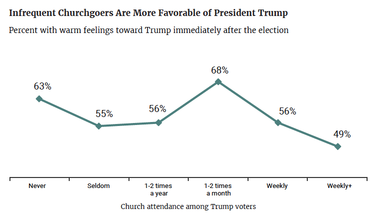

Given that many of these attitudinal patterns are inconsistent with President Trump’s own stated views, some might wonder why religious conservatives overwhelmingly voted for him in 2016. Indeed, exit polls found that 80 percent of evangelicals as well as 55 percent of frequent churchgoers voted for Trump, even after “Hollywood Access” recordings revealed Trump bragging about his own infidelity.(i)

However, right after the 2016 presidential election, religiously observant Trump voters were less enthusiastic about him than nonreligious Trump voters. While 63 percent of secular Trump voters had a “very favorable” view of Trump, a little less than half (49 percent) of very frequent churchgoers who voted for Trump agreed. Moreover, very observant Trump voters were 15 percentage points more likely than nonreligious Trump voters to say their vote was against Hillary Clinton rather than for Donald Trump (38 percent vs. 23 percent). These feelings are reflected in the exit polling data. Trump garnered a lower share of weekly churchgoers in 2016 than Mitt Romney did in 2012 (55 percent vs. 59 percent). Instead, Trump gained ground relative to Romney among infrequent churchgoers (46 percent vs. 42 percent).(ii) Nevertheless, strong majorities of Trump voters with varying rates of religious participation continue to have positive views of the president.

Figure 17

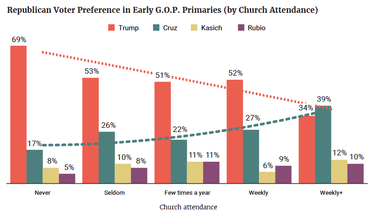

Examining the primary vote choices of Trump’s general election voters reveals a consistent pattern. Religious conservatives were less likely to vote for Trump in the early G.O.P. primaries when Republicans had several candidates to choose from.(8) Among the most devout, a plurality (39 percent) voted for Senator Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) rather than Donald Trump (34 percent).(9) However, Trump did best among those conservatives who never go to church, garnering fully 69 percent of their votes in the early primaries.

Figure 18

(8) Early primaries are categorized as the first 10 days of G.O.P. primaries.

(9) Support for Ted Cruz may have been higher than this, given that the 2017 VOTER Survey was administered after Trump had already secured the nomination and thus respondents may have wanted to say they voted for the winner.

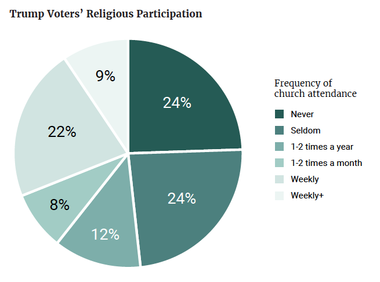

How many Trump voters attend church regularly? VOTER Survey data indicate that if church attendance does have a moderating effect on racial and immigration attitudes, it does so only for less than half of the Trump coalition. About a quarter (24 percent) of Trump voters say they never attend religious services and another quarter (24 percent) say they attend seldomly. Another 12 percent report attending a few times a year and 8 percent say they attend services a few times a month. The remaining 31 percent attend church regularly, including 22 percent who participate weekly and 9 percent who participate more than once a week.(10)

(10) It should be noted that research shows survey respondents often overreport their level of church attendance. See Daniel Cox, Robert P. Jones, and Juhem Navarro-Rivera, “I Know What You Did Last Sunday: Measuring Social Desirability Bias in Self-Reported Religious Behavior, Belief, and Identity,” Report, Public Religion Research Institute, May 17, 2014. Available at: https://prri.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/AAPOR-2014-Final.pdf.

Figure 19

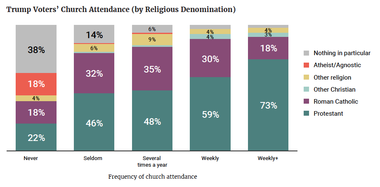

Trump voters who attend church most frequently are more likely than those who attend less to identify as a Protestant Christian. Among Trump voters who attend church more than once a week, nearly three-fourths (73 percent) identify as Protestant, 18 percent as Catholic, 4 percent as another form of Christianity (such as Mormonism), 4 percent identify with another religion, and 2 percent don’t identify with a specific religious faith. Among Trump voters who never attend religious services, a plurality (38 percent) don’t identify with any religious denomination or faith tradition, 17 percent identify as atheist or agnostic, 18 percent as Catholic, 22 percent as Protestant, and 5 percent as another religion.

Figure 20

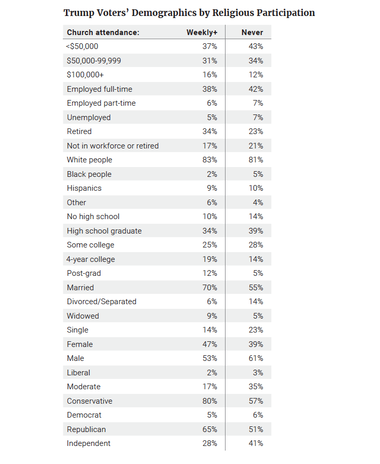

Interestingly, churchgoing Trump voters don’t look much different from their secular co-partisans on a range of demographic variables. They make about the same amount of money (although very frequent churchgoers make somewhat less). They are about equally likely to work full time (38 percent vs. 42 percent), although regular churchgoers are more likely to be retired. A similar proportion say they pay attention to the news and public affairs (64 percent vs. 62 percent). And they are both highly likely to be white (83 percent vs. 81 percent).

Table 1

However, there are a few differences. Weekly churchgoing Trump voters are more likely than secular Trump voters to be married (70 percent vs. 55 percent), be female (47 percent vs. 39 percent), and have graduated from college (31 percent vs. 19 percent). Weekly churchgoing Trump voters are also more likely to identify as conservative (80 percent vs. 57 percent) and Republican (65 percent vs. 51 percent) than their secular counterparts. Instead, secular Trump voters are more likely to identify as politically independent (41 percent vs. 28 percent) and moderate (35 percent vs. 17 percent) than weekly churchgoing Trump voters.

Taking these results together leaves us with a surprising finding: conservative, Republican, churchgoing Trump voters take more moderate positions on many culture war issues than their self-identified moderate, independent, non-churchgoing counterparts.

The positive relationship between religious service attendance and tolerance examined in this report is simply a correlation. We don’t know for sure if attending religious services causes people to become more tolerant and accepting of others with different backgrounds. But we can test whether some other demographic variable — like education, income, gender, or age — might be confounding these results. For instance, perhaps more-educated conservatives are more likely to participate in civic institutions (such as churches) and also are more likely to take more moderate positions on some culture war issues. If this were true, we might draw the conclusion that education drives these results more so than religious participation.

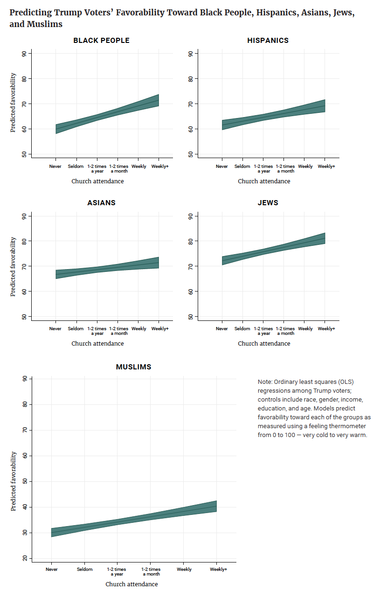

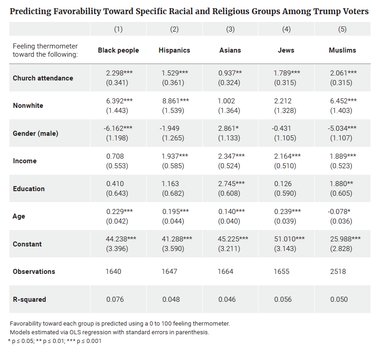

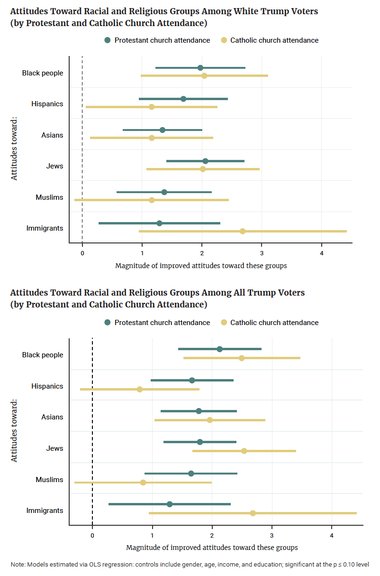

To examine this potential, we ran a statistical test (regression analysis) using church attendance as a predictor of attitudes toward racial and religious minorities while also taking into account education, income, race, gender, and age. Even when accounting for these demographic factors, increased church attendance remains a significant predictor of more favorable attitudes toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, and Muslims (Appendix A). The statistical models predict increasingly favorable attitudes toward these populations as Trump voters attend religious services more often, while holding other demographic factors constant (Figure 21).

Figure 21

Nearly three-fourths (73 percent) of Trump voters identify as either Protestant or Catholic. Might participation in either of these two faith traditions have different effects? Statistical tests suggest not. A series of tests comparing the impact of religious attendance among white Protestant Trump voters and white Catholic Trump voters reveals that participation in either faith, in most instances, is a significant predictor of improved attitudes toward racial and religious minorities.(11) Furthermore, these tests indicate that the small differences that do exist are not statistically significant. Trump voters who attend either Protestant or Catholic religious services weekly are more likely than their secular counterparts to have warm feelings toward these population groups (Appendix B).

What about other faith traditions? As there were few Trump voters who identified with religious traditions other than Protestant and Catholic, we expanded the analysis to encompass all respondents in order to examine the relationship between participation in other religious faiths and tolerance. Weekly participation in these religious traditions also significantly predict more tolerant attitudes. For instance, Muslims who attend religious services regularly are significantly more likely to have favorable attitudes toward Christians, white people, black people, Hispanics, and Asians.(12) Churchgoing Mormons are also significantly more likely to have favorable attitudes toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, Muslims, and immigrants. These findings indicate that it is not one particular religious denomination or faith tradition, but rather religious participation of some kind that may promote social tolerance.

(11) Among white Trump voters, Catholic church attendance significantly predicted more favorable attitudes toward black people and Jews, as well as immigrants at the p ≤ .05 level and toward Hispanics and Asians at the p ≤ .10 level. It did not significantly predict more favorable attitudes toward Muslims. Protestant church attendance among white Trump voters significantly predicted more favorable attitudes toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, Muslims, and immigrants. These differences may in part be the consequence of there being fewer white Catholic Trump voters (n = 733) than white Protestant Trump voters (n = 1,532) surveyed; with a lower number, there is less certainty around the white Catholic Trump voters’ estimates.

(12) Because of small sample sizes one should use caution when interpreting these results. In the survey, Muslims: n = 21; Mormons: n = 133; Buddhist and Hindu: n = 72.

To be sure, conservatives who attend church regularly don’t take the same positions as liberals on most of these issues. For instance, churchgoing Trump voters are less likely to have warm feelings toward Muslims (27 percent) compared to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 voters (66 percent). Churchgoing Trump voters are also more likely than Clinton voters to say immigration should be harder (48 percent vs. 21 percent), to oppose offering a pathway to citizenship (51 percent vs. 11 percent), to say illegal immigrants are a drain on society (61 percent vs. 10 percent), and to be frustrated with language barriers (29 percent vs. 7 percent).

Although churchgoing Trump voters are relatively more opposed to the death penalty than their secular counterparts, still more than two-thirds (68 percent) support it compared to about one-third (36 percent) of Clinton voters. And, even though an overwhelming majority (81 percent) of Trump-voting churchgoers say poverty is an important issue, that figure still falls short of the 97 percent of Clinton voters who feel similarly.

There are a few exceptions, however, where churchgoing Trump voters coalesce with Clinton voters. In particular, both groups have similarly warm feelings toward racial minorities and Jews, and they have similar attitudes about trade.

Even still, Trump voters, regardless of religious participation, take more conservative positions than Clinton voters on most issues. Thus, attending church regularly does not turn conservatives into liberals. However, religious attendance may pull conservatives in a liberal direction on key cultural issues polarizing the nation.

What about attending weekly religious services might cause conservatives to take more moderate positions on immigration, race, trade, and other issues than less-devout conservatives?(13)

First, many religious teachings specifically call for compassion and kindness. Given that 93 percent of religiously observant Trump voters identify as Christian, it is relevant to note Biblical teachings, such as those in John 15:12: “This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.”

(13) For a discussion of academic studies on the role of religious devotion in tolerance see Kenneth D. Wald and Allison Calhoun-Brown, “Religion and Politics in the United States,” Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Lanham, Md., 2010, Chapter 12, pp. 345-367, Print.

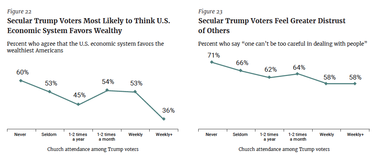

Figures 22-23

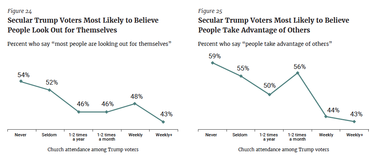

Second, perhaps religious participation instills in churchgoers a sense of personal agency and a belief in a just world. By extension, they may feel less inclined to blame “out-groups” for the challenges they face. Indeed, the survey shows that churchgoers are less likely to believe they live in a dog-eat-dog world and more likely to believe that the system is fair. For instance, the more frequently Trump voters attend church the more likely they are to believe they have a say in politics, to believe the economic system is fair, and to believe that most people try to be helpful rather than look out for themselves or take advantage of others. If churchgoers are less likely to feel as though they are victims, perhaps they are also less likely to blame external sources for the challenges they face in their lives.

Figures 24-25

Third, religious institutions provide communities that people can belong to that are not based upon their race or nationality. Thus, members do not need to rely on immutable traits such as race, ethnicity, or nation of birth to feel that they are part of something bigger than themselves. Research shows that conservatives place greater emphasis on being loyal to a community than do liberals.(iii) And so, feeling disconnected from a meaningful community may lead some conservatives to seek belonging on the basis of their race or the nation. Doing so increases exclusivity and divisiveness, and it exacerbates racial and nativist tensions.

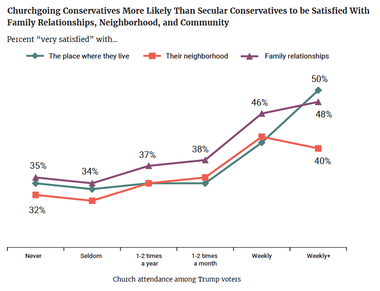

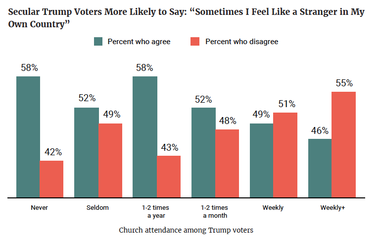

Figure 26

Indeed, we find religious people seem to feel more connected in their communities. The more frequently Trump voters attend religious services the more satisfied they report being with the place where they live, their neighborhood, and their family relationships. For instance, very devout Trump voters are about 15 percentage points more likely than nonreligious Trump voters to feel satisfied with their communities and family relationships.

Consistent with this pattern, religious Trump voters are more likely to feel comfortable and at home in the United States, while secular Trump voters feel like strangers. While 58 percent of secular Trump voters agree that “these days I feel like a stranger in my own country,” almost the same share (55 percent) of religious Trump voters disagree.

Figure 27

The results of this analysis indicate that religious participation may have a moderating effect on our politics, particularly on matters of race, immigration, and identity. They further suggest that private institutions in civil society — outside of the domain of government and public policy — may serve an important function in reducing polarization and racial tensions and helping people find common ground. However, several important forces may diminish these possible effects.

First, partisanship may lessen the differences between religious and nonreligious conservatives as they unify behind President Trump. For instance, Trump’s executive order restricting travel to the U.S. from several Muslim-majority countries and negative trade rhetoric may override the natural differences that emerge between religious and nonreligious conservatives. Thus in some circumstances the president may reduce the impact of religious participation on people’s opinions about key cultural issues.

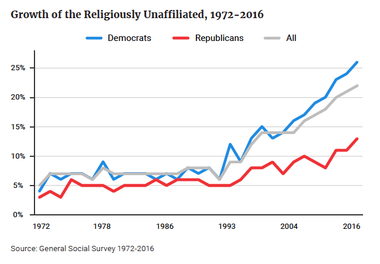

Second, record numbers of people are leaving organized religion. Data from the Public Religion Research Institute finds that, since 1992, the number of people leaving their faith traditions has quadrupled among the general public and tripled among conservatives.(iv) Thus, a potential moderating force among conservatives has been receding. Research has found that conservatives tend to care more about being a part of, and loyal to, a community.(v) But as conservatives withdraw from religious participation, they may redraw the boundaries of their group identity along the lines of immutable traits such as ethnicity and nation of birth rather than something people can choose. For instance, this could potentially bolster support for white nationalism and the so-called alt-right movement.

Figure 28

Third, as many people view religious institutions through the lens of the L.G.B.T. culture wars, they overlook and thus dismiss these civil institutions as a possible source of tolerance and moderation on other issues. They incorrectly assume that if religious people are less accepting of sexual minorities they may also feel less favorable toward racial and religious minorities. In addition, many critical of religious affiliation may assert that plenty of nonreligious people are tolerant of diversity, making religious participation seem unnecessary to foster tolerance — but this phenomenon is found primarily on the left. Many have not considered whether religious observance has differing effects among conservatives and liberals. Thus, some view religious participation as both being unhelpful and pernicious to the cause of tolerance and social harmony. This view is further reflected and promoted through pop culture and entertainment that depicts religious conservatives as villainous or backward. Some may hope that encouraging conservatives to disengage from religion will make them more tolerant. However, these data provide some indication they may not become more tolerant, but rather become intolerant of different groups.

In sum, a force that may moderate conservatives on certain issues and reduce polarization is on the decline and pop culture is reaffirming the trend. But if interpretation of this data is any guide, doing so may backfire. While it may be true that declining religious participation has calmed the culture wars over moral traditionalism and L.G.B.T. rights, it may also come at the expense of fueling deeper resentment along the lines of race, ethnicity, and nativity. While government certainly should have no role promoting religion, these data indicate there may be unexpected negative consequences should government or popular culture be used with intent to diminish people’s ability or desire to participate in religious traditions.

This table shows statistical model estimates predicting favorability toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, and Muslims, respectively, using a “feeling thermometer,” which asks respondents to rate their feelings toward the following groups using a scale of 0 to 100 where 0 means they feel very cold and unfavorable and 100 means they feel very warm and favorable toward the group. All variables are coded so that higher values indicate more favorable feelings toward each of the following groups. These models show that greater church attendance significantly predicts more favorable attitudes toward black people, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, and Muslims even when taking into account the effects of other variables.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.