Elections, Ideology, Political Parties

Key Findings

It is a truism of modern American politics that the United States is a deeply divided nation. By almost all measures, the two parties are further apart from each other, both at the elite level, and in the electorate, than in the past. There are more and more politically lopsided counties,(i) and only a small percentage of states and congressional districts swing from one party to another.(ii) Partisan unity scores in Congress are very high.

Yet, while the parties are far apart from each other, there are also tensions within them — tensions that were clearly on display in the 2016 primaries. In both parties, primaries revealed rifts, though Democrats were generally more cohesive than Republicans. As it appeared that Hillary Clinton would win the election, it became fashionable for political observers to write about the coming Republican civil war.

While Trump’s victory quieted some of that talk, there are still deep tensions within the Republican coalition, divisions that are now re-emerging as the exigencies of legislating return. Most notably, the nativist populism on which Donald Trump campaigned is at odds with much of what Republicans have traditionally embodied. It is unclear how Trump can both deliver the policies he promised while holding onto support from the more traditional conservatives who stuck with him.

In this essay, I investigate the nature of the political conflict both between and within the two major political parties. I will argue that the primary conflict structuring the two parties involves questions of national identity, race, and morality, while that the traditional conflict over economics, though still important, is less divisive now than it used to be. This has the potential to reshape the party coalitions.

This essay takes as its starting point a few basic points of theory.

First, that we should view politics across multiple issue dimensions. Rather than simply describing political alignments in terms of “left” and “right,” I argue that we should understand that voters are not ideologically coherent (in that they endorse the party line across most issues), but instead have different mixes of left and right views across different issues.(iii) Thus, the party coalitions and resulting majorities depend on which of many potential issues form the dominant conflict, and which conflicts are subsidiary.(iv)

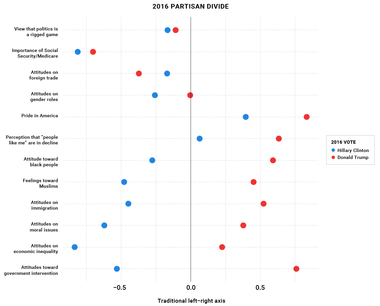

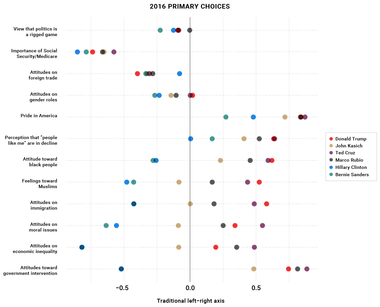

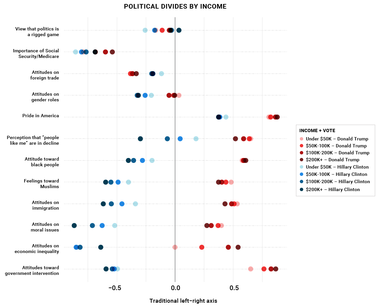

Figure 1 reports averages among Clinton and Trump voters along the 12 issue dimensions.

Figure 1

First, we can see there are some issues that don’t strongly divide voters. Most notably, there is no clear difference on how much Clinton versus Trump voters think the political system is rigged — that elections don’t matter, that they don’t have a voice, and that elites don’t care about them. Therefore, the claim that this was an election about disaffected voters does not seem to hold up well.(v) Or, at the very least, if some voters were disaffected, it did not help one candidate more than the other.

Another area of agreement is that voters on both sides consistently view Social Security and Medicare as important, which is consistent with long-standing, cross-partisan voter support for a strong social safety net. Also, voters in both parties are skeptical of trade, though Trump voters are slightly more skeptical of trade than Clinton voters.

Moving to issues that divide the parties, there is a clear division on concern about inequality and support for active government, consistent with what we have come to expect from the parties.

Trump voters tend to have more traditional gender attitudes than Clinton voters, but the divisions are not wide. Certainly, gender attitudes are not central to the party divide.

We should understand that voters are not ideologically coherent, but instead have different mixes of left and right views across different issues.

Though it is possible to describe many potential issue dimensions (I will describe 12 here), there is considerable evidence that we can capture much of what happens in today’s politics through two of them, an economic and a social/identity dimension.v Basically, how much should government redistribute wealth, and what does it mean to be an American?

Historically, Americans have held left-of-center views on the first question, and right-of-center views on the second question.(vi) Since our two major political parties hold consistent views on both issues, but not all voters in both parties share this consistency, some portion of the electorate has to decide which of these two issues is more important to them and make compromises on the other issue.(vii)

One way to understand the 2016 election, then, is to note that by making questions of national identity more salient, Donald Trump succeeded in winning over “populists” (socially conservative, economically liberal voters) who had previously voted for Democrats. The VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey) data support this.

Trump’s candidacy has brought more economic liberals into the Republican Party, moving the party’s center of gravity on these issues to the left. Trump has also moved the party to a much more nativist position on questions of national identity.

Both of these shifts are creating some strain within the Republican Party coalition, which could force splits. Although the Democratic Party is more unified, it is not immune to a crack up as well. The parties respond to each other, seeking to steal each other’s voters as available. Moreover, imposing a two-party system on a multi-dimensional issue space means that the larger the coalition, the more tenuous it is.

Let’s now turn to the VOTER Survey data to get at some of these bigger questions. Specifically, I will focus on:

Before I get started, a quick note on how I am using the VOTER Survey data: I have put together 12 indexes measuring opinion on issues that were salient during the campaign, all of which have been offered in various interpretations as important factors. All variables are created by scaling all responses from -1 (a traditional left position) to 1 (a traditional right position), and then averaging across questions for each respondent.

The indexes and the VOTER Survey questions that inform them are as follows:

The View That Politics is a Rigged Game

The Importance of Social Security/Medicare

Attitudes on Foreign Trade A battery of questions on the costs/benefits of free trade.

Attitudes On Gender Roles A battery of questions on the role of women in society.

Pride in America

The Perception That “People Like Me” Are Losing Ground

Attitudes Toward African-Americans A battery of racial resentment questions toward African-Americans.

Feelings Toward Muslims

Attitudes on Immigration

Attitudes on Moral Issues

Attitudes on Economic Inequality

Attitudes Toward Government Intervention

The measures here are “absolute” measures as opposed to “relative.” That is, I took the responses to the VOTER Survey questions as given, rather than rescaling the indexes to set the median score at zero. While this transformation would have made for a more symmetrical presentation, it ignores the fact that Americans may hold left-of-center views on some issues and right-of-center views on other issues. These imbalances and asymmetries are important to represent clearly. They are the raw material of both the strategic coalition building and coalition instability described in this chapter.

Supporters of Clinton and Trump are very polarized on identity and moral issues. Views on economic issues are more of a mix.

Trump supporters tend to have more pride in America than Clinton supporters do, and they are more likely to think that their group is in decline. However, these divides are not as significant as many media narratives portrayed them to be.

Divides get much wider as we move toward questions of race and national identity. Trump voters have more negative attitudes than Clinton supporters about African-Americans, are much less supportive of immigration, and have much more negative feelings toward Muslims.

On moral issues (abortion, same-sex marriage, transgender bathrooms), there is an even larger divide between Clinton and Trump supporters in the general election. As we will see later, this was one area where Trump’s core supporters looked more moderate than Ted Cruz supporters. However, these questions continue to divide the two parties.

Finally, the traditional issues that have divided the two parties, questions of inequality (whether the rich have too much money and should be taxed more), and questions about government’s involvement in the economy (whether government should intervene more or less and whether government should regulate business more or less) continue to divide the parties the most.

To summarize, supporters of Clinton and Trump are very polarized on identity and moral issues. Views on economic issues are more of a mix. Both candidates’ supporters are generally supportive of the social safety net, and somewhat concerned about trade. Yet they diverge very much on how concerned they are about inequality, and how actively they want to see government regulate business and intervene in the economy.

The 12 dimensions provide nuance, but for simplicity’s sake, it is easier to combine these indexes into the two main dimensions that organize public opinion: questions of economics and questions of culture/social/national identity.

To do this, I created two new indexes:

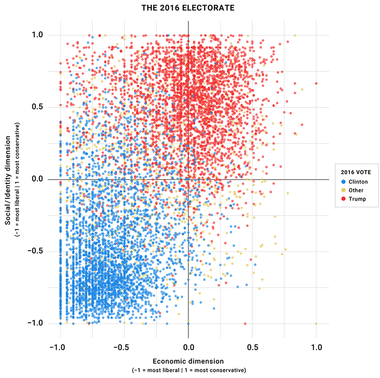

This allows us to plot all respondents on a single scatterplot, shown here.

Figure 2

Most Clinton supporters cluster in the lower-left corner: liberal on both economic and identity issues. Trump supporters cluster in the upper-middle: conservative on identity issues, and somewhat conservative on economic issues.4 Trump general election voters, however, are more widely dispersed on economic issues, ranging more broadly from liberal to conservative.

To simplify further, we can break the electorate into four types, based on their position in the four quadrants of Figure 2:

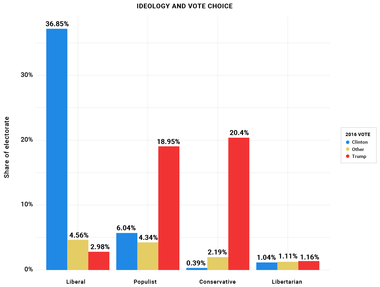

Figure 3

Not surprisingly, Clinton wins overwhelmingly in the liberal quadrant, and Trump wins overwhelmingly in the conservative quadrant. However, it is also worth noting that Clinton won only 83.4 percent of liberals, while Trump won 6.3 percent of liberals. By contrast, Trump won 90.2 percent of conservatives, and Clinton won almost no conservatives.

While Clinton relied overwhelmingly on liberals, Trump’s general election support was split evenly between conservatives and populists — of the electorate, 20.4 percent were conservatives who supported Trump, 19.1 percent were populists who supported Trump.

This mirrors a split in the Republican Party between populists and conservatives. They are generally unified on identity issues, and split on economic issues. Democrats, by contrast, are much more unified. Almost all of Clinton’s support came from the liberals.

Notably, Trump outperformed Clinton by about a 3-to-1 margin among the populists. Only 5.7 percent of the electorate were populists who supported Clinton. Another 4.3 percent was populists who supported somebody else.

Also worth noting: libertarians split almost equally between Clinton, Trump, and others (mostly Johnson). They are, however, a very small proportion of the overall electorate.

One important aspect of these alignments is that there is more overlap between both candidates’ supporters on economic issues than there is on identity issues. Put another way, the parties are more clearly divided on social/identity issues than they are on economic issues.

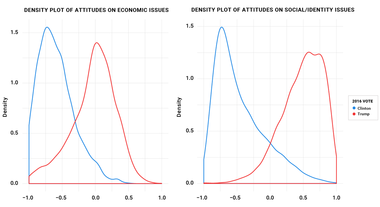

We can see this even more clearly by looking at density plots (Figures 4 and 5), which represent the distribution of voter opinion on economic and identity issues.

These density plots help demonstrate that there is noticeably more overlap between the two camps on economic issues than there is on social/identity issues. Specifically, 16.4 percent of Clinton voters are to the right of the median position on the economic index, while 17.0 percent of Trump supporters are to the left of the overall median position on the economic index. By contrast, only 11.5 percent of the Clinton supporters are to the right of the median on the social/identity index, while just 10.2 percent of the Trump supporters are to the left of the overall median position on the social/identity index.

Figures 4 and 5

How did we go from Obama to Trump? The simple answer is that Trump picked up enough Obama voters in key states to win. This begs the obvious question: why?

To start, I break the electorate into six segments: Obama to Clinton voters, Obama to Trump voters, Obama to other voters, Romney to Trump voters, Romney to Clinton voters, and Romney to other voters.

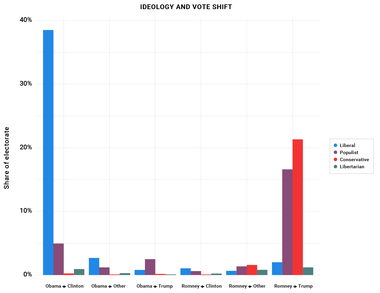

Continuing with our quadrant analysis, we can see how the electorate breaks down along these four quadrants in line with 2012 to 2016 shifts.

Figure 6

The data here confirm the main story we’ve all been told. The Obama to Trump voter was overwhelmingly a populist — liberal on economic issues, conservative on race issues.

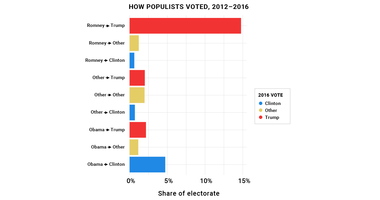

We can now dig in more deeply on the populists in Figure 7, which looks at how voters who fall into the populist category voted from 2012 to 2016.

Figure 7

First, observe that a little more half these populists were already Romney supporters. Of the 29 percent of the electorate that is populist, almost 16 percent were already Republican voters in the 2012 presidential election. Trump kept 93 percent of these populists voting Republican, losing very few to other candidates, and even fewer to Clinton.

Of the remaining 13 percent of the electorate qualifying as populists, about 8 percent of electorate had voted for Obama in 2012, while another 5 percent of the electorate had voted for someone else.

Among those populists who voted for Obama, Clinton did terribly. She held onto only 6 in 10 of these voters (59 percent). Trump picked up 27 percent of these voters, and the remaining 14 percent didn’t vote for either major party candidate.

It is also worth noting that Trump did surprisingly well with the disaffected populist voters who had supported neither Obama nor Romney in 2012. More than 4 in 10 (43 percent) shifted to voting for Trump, while just fewer than 1 in 6 (15 percent) shifting to Clinton. The remaining 42 percent again withheld their support for a major party candidate. While this group is not a huge percentage of the electorate, in a close election every little bit matters.

There is less of a clear story about the Romney voters who failed to support Trump. However, Romney to Clinton voters were predominantly liberals on the issues, suggesting that they were already in line with Clinton. (As we will see later, they were mostly weak liberals, closer to the upper right-hand portion of the liberal quadrant.)

The obvious question is what happens to these voters in transition. If Republicans hold onto the Obama to Trump voters, but win back some of the Romney to other voters, or even Romney to Clinton voters, Republicans will be the majority party. Likewise, if Democrats can hold onto the Romney to Clinton voters, and win back some of the Obama voters who did not vote for Clinton, they will be in a strong position.

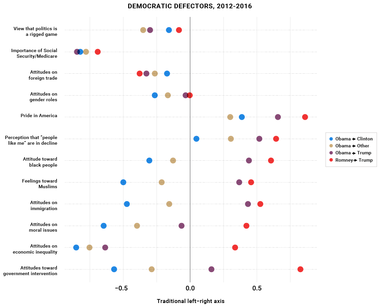

To gain a little more insight into these floating voters, we can return to our 12-issue dimension view. Let’s start with the Obama voters, using Romney to Trump core Republican voters as a point of comparison.

Figure 8

The data suggest that the main divide within the Democratic Party electorate is about attitudes toward the establishment and the existing order than it is about specific issue positions (with the exception of trade policy).

Looking at these issues more closely, we can see that the Obama to Trump voter looks very much like Romney to Trump supporters on attitudes toward African-Americans, feelings on immigration, and attitudes toward Muslims. Interestingly, the Obama to Trump voter is not as conservative on moral issues, and looks like a Clinton voter on concerns about inequality. However, the Obama to Trump voter is in the middle (on average) on the role of government in the economy.

However, we already knew Obama to Trump voters were populists. Perhaps more interesting are the Obama voters who supported neither Clinton nor Trump. For the most part, they are more conservative than Obama to Trump voters, though slightly more disaffected about the nature of the political system. Though many on the far left argue that Clinton would have won had she been more progressive and excited more Sanders voters, the data here suggest that Clinton may have lost some Democratic voters because her campaign was too left leaning, particularly on the identity and social issues, but perhaps also some issues of government intervention as well. Again, these averages mask a certain degree of variation, so one should be cautious of overgeneralizing.

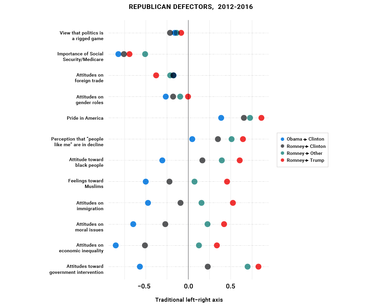

Now let’s turn to Republican voters.

Figure 9

The Romney to Clinton voters are like the Obama to Trump voters in one respect. They seem to have voted primarily based on social/identity issues, on which they were considerably closer to core Democratic voters than Republican voters (especially on attitudes toward Muslims). They also were closer to Democrats regarding attitudes on economic inequality.

The more interesting category here are the Romney voters who could not support Trump but also did not want to vote for Clinton. For the most part, they are slightly to the left of core Republican voters who supported both Romney and Trump.

Trump’s biggest enthusiasts within the party are Republicans who hold the most anti-immigration and anti-Muslim views, demonstrate the most racial resentment, and are most likely to view Social Security and Medicare as important.

However, on two issues — immigration and attitudes toward Muslims — the gap is a little wider between those voters and Romney to Trump voters. They also tend to be the most traditionally free market on the social safety net and free trade. This fits with the general story reported in the press: many of these voters were principled conservatives for whom these distinctions made a big difference, and who felt somewhat uncomfortable with the far-right position on some of the identity issues (even if they were moderately conservative on these issues).

Now let’s turn to the disagreements within the parties.

The topline observation here is that Republicans are more internally divided than Democrats. One way to see this is to arrange our 12 issues by primary choice.

Figure 10

Let’s start with Democrats. Although there was a bitter fight between Sanders and Clinton, it turns out that their voters are not all that different on most issues.

There are three notable points of difference. Sanders supporters were notably less enthusiastic about trade deals. This was a point of contention between Clinton and Sanders, so the difference we see here makes sense. Sanders supporters were also a little less enthusiastic about America and its history, and they evinced more pessimism about people like them. Yet, they are indistinguishable from Clinton supporters on concern for inequality and value of government activism. On the social and identity issues, they are also largely indistinguishable from Clinton supporters.

Thus, to the extent that the Democratic Party is divided, these divisions are more about faith in the political system and general disaffection than they are about issue positions.

By contrast, Republican voters are more split. For the most part, Trump and Cruz supporters look fairly similar, though Cruz supporters are considerably more conservative on moral issues, and notably less concerned about inequality and the social safety net, and more pro-free trade. In other words, Cruz voters were more likely to fit the description of traditional

conservatives.

For the most part, Kasich supporters are the true moderates, caught in between the two parties on almost every issue, both economic and social. Kasich supporters come closest to Democrats on their feelings about immigration and about Muslims specifically. Rubio supporters tend to come between Kasich supporters, and Trump and Cruz supporters on the social/identity issues, but are generally more conservative on economic issues — typically somewhere to the right of Trump supporters.

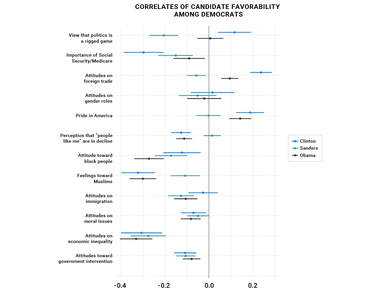

Another way to assess the party divisions is to look at how voters’ favorability toward different leading party politicians correlates with their issue positions. To do this, I report regression results in which candidate favorability is estimated from partisans’ positions on the 12 indexes. The dots represent the estimated relationship (holding all other issues constant), and the lines represent the standard error of the estimate.

First, let’s look at the Democratic Party.

Figure 11

Looking at the correlates of candidate favorability, we can more clearly see the potential divide in the Democratic Party. Again, it is more about disaffection than issue positions. The strongest predictor of Sanders support (holding all else constant) is a sense that the system is rigged. Clinton’s biggest boosters, by contrast, are more comfortable with the system as is, are less likely to see things getting worse, and are generally prouder about America. They are also more supportive of free trade. Interestingly, support for Muslims is noticeably more highly correlated with support for Clinton than for Sanders. This is somewhat surprising.

Still, the data suggest that the main divide within the Democratic Party electorate is about attitudes toward the establishment and the existing order than it is about specific issue positions (with the exception of trade policy). Democrats are also quite unified on social/identity issues.

Could these divides grow? "Certainly, they might, especially if the central question among Democrats becomes how much to swing right on economic issues in hopes of capturing the limited number of socially liberal, economically conservative Republicans." Still, to the extent that many of these divisions are establishment/antiestablishment divisions, they are somewhat muted by Democrats now being the opposition party. By contrast, had Hillary Clinton become president, these disagreements might have widened, since governing requires the kind of compromise and incrementalism that would be most likely to drive the Sanders wing of the party into rebellion.

The data suggest that the main divide within the Democratic Party electorate is about attitudes toward the establishment and the existing order than it is about specific issue positions (with the exception of trade policy).

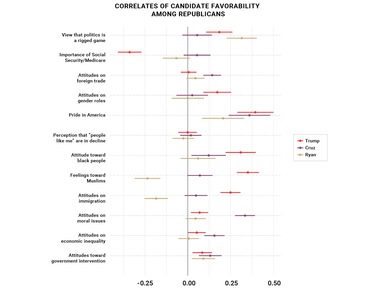

Now let’s turn to the Republican Party. I include Trump and Cruz here, but also Paul Ryan, to give us another perspective on how things might move forward, since Ryan is now a much more prominent Republican figure than either Kasich or Rubio.

Figure 12

Looking at divides within the Republican Party through the correlates of enthusiasm toward different leading figures, we can see that Trump’s biggest enthusiasts within the party are Republicans who hold the most anti-immigration and anti-Muslim views, demonstrate the most racial resentment, and are most likely to view Social Security and Medicare as important.

By contrast, the strongest predictor of support for Ted Cruz is a set of strongly conservative views on moral issues, and somewhat pro-free trade views. The distinguishing predictor of strong support for Paul Ryan is a set of pro-immigration and pro-Muslim beliefs, and a high level of faith in the existing political system. However, since pro-immigration and pro-Muslim views are in short supply among Republicans, this does not bode well for Paul Ryan.

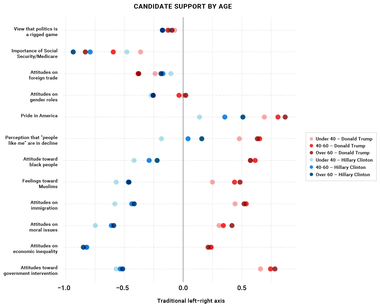

One way to assess where the parties are headed is to look at how voters within the party vary by age cohort.

Trump’s biggest enthusiasts within the party are Republicans who hold the most anti-immigration and anti-Muslim views, demonstrate the most racial resentment, and are most likely to view Social Security and Medicare as important.

Sticking with the 12-issue view, we can break down both Clinton and Trump voters into three age groups: under age 40, ages 40-60, and over age 60. In both parties, younger voters are more liberal than older voters on social/identity issues, but this varies somewhat by issue. Notably, among Trump supporters, the age gap is nonexistent on resentment toward African-Americans, and very small on immigration. There is a wider gap on feeling toward Muslims, with old Trump voters being more anti-Muslim. However, the gaps between the parties on all these issues dwarf the gaps within the parties. Even if demographic replacement happens within the parties, these divisions would remain.

Figure 13

On the economic issues, there is also not much of a difference by age, except for on Social Security and Medicare. Presumably, younger voters care less about these issues because they do not expect to receive benefits anytime soon. Younger voters in both camps are also a little more pro-trade than older voters.

The widest within party variation by age cohort is within the Democratic Party on the indexes measuring pride in America and the perception that “people like me” are losing ground. Younger Democrats are both the most optimistic about their own future, but the least enthusiastic about America. To the extent that politics is increasingly organized around a conflict over ethnonationalism versus multicultural cosmopolitanism, the vanguard of this struggle is younger Clinton voters opposed to older Trump voters.

Another important determinant of what direction the parties may be going is where the highest-income partisans want the parties to head, since they provide the funding for party committees and candidates, acting effectively as a “donor class” that can exert a powerful pull on the priorities and positions of the parties and their candidates.

In both parties, this donor class is both more conservative on economic issues and more liberal on social issues, as compared to the rest of the party. However, there is a slight but notable asymmetry between the two parties on identity issues. Among Democrats, the donor class is notably to the left of the working class on these issues. Among Republicans, the donor class is also to the left of the working class on identity issues, but only slightly. This suggests that Democrats could feel more pressure to move to the left on identity issues, while Republicans will stay where they are, further polarizing the parties on identity issues.

Figure 14

A Final Note On Immigration

Since immigration is emerging as a dominant issue, it is worth asking in a little more detail what impact it might have on the future of the party coalitions. Already, we saw that in 2016, many of the party switchers appear to have been motivated by identity issues. Obama to Trump voters were much more conservative on identity issues than Obama to Clinton voters, and Romney to Clinton voters were much more liberal on identity issues than Romney to Trump voters.

Are there still voters whose political beliefs are at odds with the candidate they supported in 2016? It turns out there are.

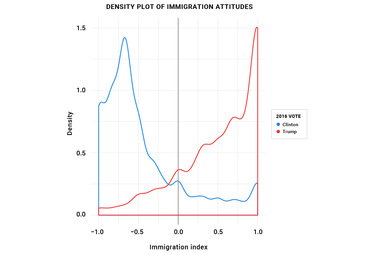

First, to get a sense of the range of attitudes on immigration, below is a density plot of the immigration index among Clinton and Trump supporters.

Figure 15

As we have seen already, the Clinton and Trump voters are already fairly polarized on immigration attitudes and identity issues generally. Notably, almost a third of Trump voters (31.8 percent) responded with the strongest anti-immigration attitude on all three VOTER Survey questions. By contrast, 1 in 6 (16.2 percent) of Clinton supporters responded with the strongest pro-immigration attitudes on all three VOTER Survey questions.

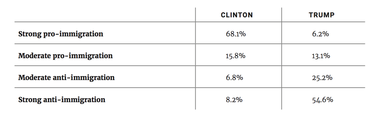

More broadly, we can break voters into four categories based on their responses to the questions:

The breakdown among Trump and Clinton supporters is as follows:

By this count, 15 percent of Clinton supporters hold anti-immigration attitudes, while 19.3 percent of Trump supporters hold pro-immigration attitudes. Alternatively, 83.9 percent of Clinton supporters picked the candidate that they agreed with on the issue, while 79.8 percent of Trump supporters picked the candidate that they agreed with on the issue.

What about the voters who picked the candidates with whom they disagreed? There are three possible overlapping explanations. One is that these voters picked the candidates for other reasons despite disagreeing with their position on immigration (such as, perhaps, their position on taxes). Two is that immigration was not an important issue to these voters so they did not consider it. Three is that the voters were not really aware of the differences between the two candidates on immigration, but might have chosen differently if the issue were more salient.

Of particular interest are the voters who are most mismatched: the 8.2 percent of Clinton supporters who have strong anti-immigration attitudes, and the 6.2 percent of Trump supporters who have strong pro-immigration attitudes.

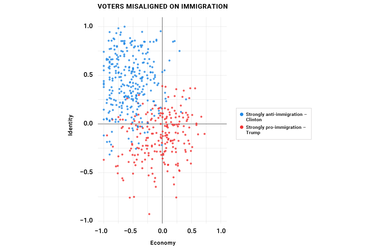

Placing these voters on the two-by-two economics versus identity grid reveals a few insights.

Figure 16

As we might expect, almost all the anti-immigration Clinton supporters are in the populist quadrant, torn between their economic liberalism and identity conservatism. Presumably, they will continue to be torn, and much may depend on how they break.

The misplaced Trump supporters are mostly a mix of libertarians and liberals. The libertarians make sense — like populists, they are torn between their social liberalism and economic conservatism, and like anti-immigration Clinton supporters, they voted on economic issues, not social/identity issues. More puzzling are the Trump supporters who are liberal on both identity and economic issues. Perhaps they are misinformed, or perhaps they are single-issue voters on some other set of issues.

Since the VOTER Survey does not directly ask respondents to place the candidates on the issue, we cannot answer questions about being misinformed directly. However, we do know something about the importance of the issue.

Among the strongly anti-immigrant Clinton supporters, 48.4 percent said immigration was “very important” and 36.7percent said it was “somewhat important.” Among the strongly pro-immigration Trump supporters, 31.5 percent said it was “very important” while 50.2 percent said it was “somewhat important.” Among all voters, 46.1 percent said immigration was very important, and 37.5 percent said it was somewhat important.

In general, strongly anti-immigration Clinton supporters tend to be less educated (38 percent of them only had a high school education, while only 25 percent had a bachelor’s degree or more), while pro-immigration Trump supporters were better educated (43 percent had a bachelor’s degree or more, only 26 percent had a high school education or less).

Strongly anti-immigration Clinton supporters were 74 percent white (higher than the overall percentage among Clinton supporters), while strongly pro-immigration Trump supporters were 80 percent white (lower than the overall percentage among Trump supporters).

Among anti-immigration Clinton voters, 39 percent reported supporting Clinton in the primary, as compared to 17 percent saying they supported Sanders. Among pro-immigration Trump voters, 25 percent said they supported him in the primary, as compared to 13 percent for Cruz and 12 percent for Kasich.

What these numbers suggest is that anti-immigration Clinton voters may not have been fully aware of the differences between the two parties on immigration, while pro-immigration Trump voters may have been more likely to be aware, but did not care enough about that issue. If the issue becomes more salient, both groups may have to decide whether they care deeply enough about the issue to shift their party loyalty, or whether they care enough about their party loyalty to shift their position. Since the anti-immigration Clinton voters reported caring about the issue more and are less educated, they may be more likely to shift if the issue becomes more salient. On the other hand, Democrats should be able to win the Trump voters who are liberal on both economic and social issues in the future, unless these voters have some other strong reason for supporting Republicans that this analysis has failed to detect.

Let’s review the answers to the four questions this essay posed.

What Divides The Parties Now?

The parties are divided on both social/identity and economic issues, but more so on identity issues. The gaps between the Clinton and Trump voters on questions of racial resentment, immigration, attitudes toward Muslims, and moral issues are consistently wide. There is very little overlap between the two camps on these issues.

By contrast, although the parties are divided on economic issues, there is more overlap. Particularly in the Republican Party, there are a wide range of views on economic issues, now that the party has expanded to include more and more populists who were formerly Democrats.

What Shifted From 2012 To 2016?

The main shift between 2012 and 2016 is that Republicans made gains among the populists (voters who are economically liberal and conservative on social/identity issues). In 2012, Romney outperformed Obama by about a 2-to-1 margin among these voters. In 2016, Trump outperformed Clinton by about a 3-to-1 margin among these voters. The data here strongly suggest that the increasing salience of identity issues in the campaign caused the shift.

It also cost Republicans some votes. Many of the Romney voters who supported Clinton did so because they were uncomfortable with Trump’s far-right positions on immigration and other identity issues.

What Are The Divisions Within The Parties?

Both parties have internal divisions, though the divisions within the Republican Party are probably greater, since Republicans are about equally divided between economically liberal populists and more free-market-oriented conservatives. Republican primaries revealed a Kasich faction that is consistently more moderate across issues, a Trump faction that is more liberal on economic issues but more conservative on identity issues, and a Cruz faction that is more free market on economic issues and particularly conservative on moral issues.

Democrats are less divided on the substantive issues, but somewhat more divided in disposition, with Sanders supporters evincing more anti-establishment disaffection, and Clinton supporters having more faith and enthusiasm toward the political system overall.

There are still enough cross-pressured voters that party coalitions could continue to shift.

Where Are The Parties Headed? Much of the future of the parties will depend on the issues that emerge and dominate our politics. Early indications suggest that Trump was serious about his ethnonationalist agenda, which will keep identity issues, especially immigration, at the center of our politics. If this happens, it may put pressure on the remaining pro-immigration Republicans and the remaining anti-immigration Democrats (some remain in both camps), further realigning the parties. Democrats may also be pressured to move further left on these issues, given that both younger voters and the party’s donor class are quite far to the left on identity issues. If so, American politics would become further polarized along questions of culture and identity.

Since Republicans have picked up more economically liberal voters (and may continue to do so since there are still some populists who vote for Democrats), it may be harder for Republicans to continue to push a traditional conservative free-market agenda. If so, this would leave conservatives with little place to go. Democrats might move right a little bit on economic issues, but they are limited by where their voters are on the issue. In addition, a move rightward might activate more of the anti-establishment sentiment that could potentially cause a rift in the Democratic Party.

Voters might also change their beliefs in line with their party. Since Trump is taking on many positions that have traditionally not been Republican positions (especially on economic nationalism), we may see Republican voters shifting their beliefs. This would further isolate remaining conservatives with moderate positions on immigration (i.e., the Paul Ryan Republicans). However, at this point the Democratic Party does not offer an obvious home to these voters.

Again, much depends on which issues become most salient, and which political elites emerge as leaders and how they package issues. There are still enough cross-pressured voters that party coalitions could continue to shift.

About the Author

Lee Drutman is a senior fellow in the program on political reform at New America. He is the author of "The Business of America is Lobbying" (Oxford University Press, 2015) and winner of the 2016 American Political Science Association’s Robert A. Dahl Award.

The views and opinions in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Democracy Fund.

Subscribe to our mailing list for updates on new reports, survey data releases, and other upcoming events.